10 Takeaways from International Design Conference 2018

More and more, designers are giving special attention to the human experience and its role as the fundamental motivator of design, but thinking about humans, design, tech, and the future is not straightforward. September’s International Design Conference (IDC), an annual event organized by the Industrial Designers Society of America (IDSA) considered these topics by bringing together “leading design minds from around the world” to talk about human-centered design in practice. Speakers ranged from storytellers at Facebook to a shoe designer at Nike. Along the way, vendors from Google, Autodesk, Keyshot, and more came to show off their products.

I went to IDC 2018 with several goals in mind. First, I aimed to learn from and capture diverse perspectives in design on behalf of EDR. As a fellow, I reach across disciplines to enrich the practice. At the conference, I was immersed in creative thinking, and I was excited to be a neophyte in a room full of top designers in their fields. I also attended to make new connections for EDR and for myself as a prospective designer.

Practitioners and enthusiasts of industrial design, interaction design, UI/UX design, and architecture gathered to share their experiences and connect with one another.

Why Should Architects Care About Industrial Design?

We are all creative people in people-centered industries working with diverse toolkits. Every once in a while, architects might want to get out of the bubble of a project and think from a different perspective, borrowing whatever strategies are useful from the sister discipline’s toolkits. Architects often work with tools developed by industrial designers in the design process and might even partner with industrial designers on a project, so being familiar with their practices might also be pragmatically constructive.

The following takeaways represent an overview of the perspectives that we as designers can utilize to continue to grow a more people-oriented practice.

1. People live different versions of the same intended experience.

When we design an environment or experience, it is tough to consider how that experience might vary between people. John Maeda, a famous figure at the intersection of design, technology, told a story about a running accident that broke his arm. Breaking a bone changed his priorities completely. Instead of contemplating a detail in a project, he thought, “Wow, my arm hurts!” and, “I can’t even open my sketchbook.” His story highlighted a point of broader importance in architecture: personal priorities are impactful and can be unexpected; diversity must be considered in design for people.

2. The smarter you are, the dumber you get.

We as designers should continually push ourselves to think of an issue from other perspectives. Kathleen Brandenburg (IA Collaborative) told a story about her nine-year-old self in a tractor with her father, who designed the equipment. She asked why the “fast” and “slow” settings were symbols for a rabbit and a turtle rather than written words for speed. He said that, actually, many of the people he designs for cannot read. Reflecting on this experience, she realized that design should be accessible to all and should enhance usability. If designers are so immersed in their own niches of expertise, they are missing out on other important sources of information. Designers should “live the problem” to design the solution. In architecture, this translates to understanding clients’ and occupants’ values and how they use spaces to more successfully create an effective space that facilitates desired activities and interactions.

Brandenburg went on to explain that thinking with science (controlled variables, measuring, evidence) and design (multiple inputs and systems, open-ended and generative) together can uncover powerful insights. Designers should use multiple inputs to inspire and inform their work.

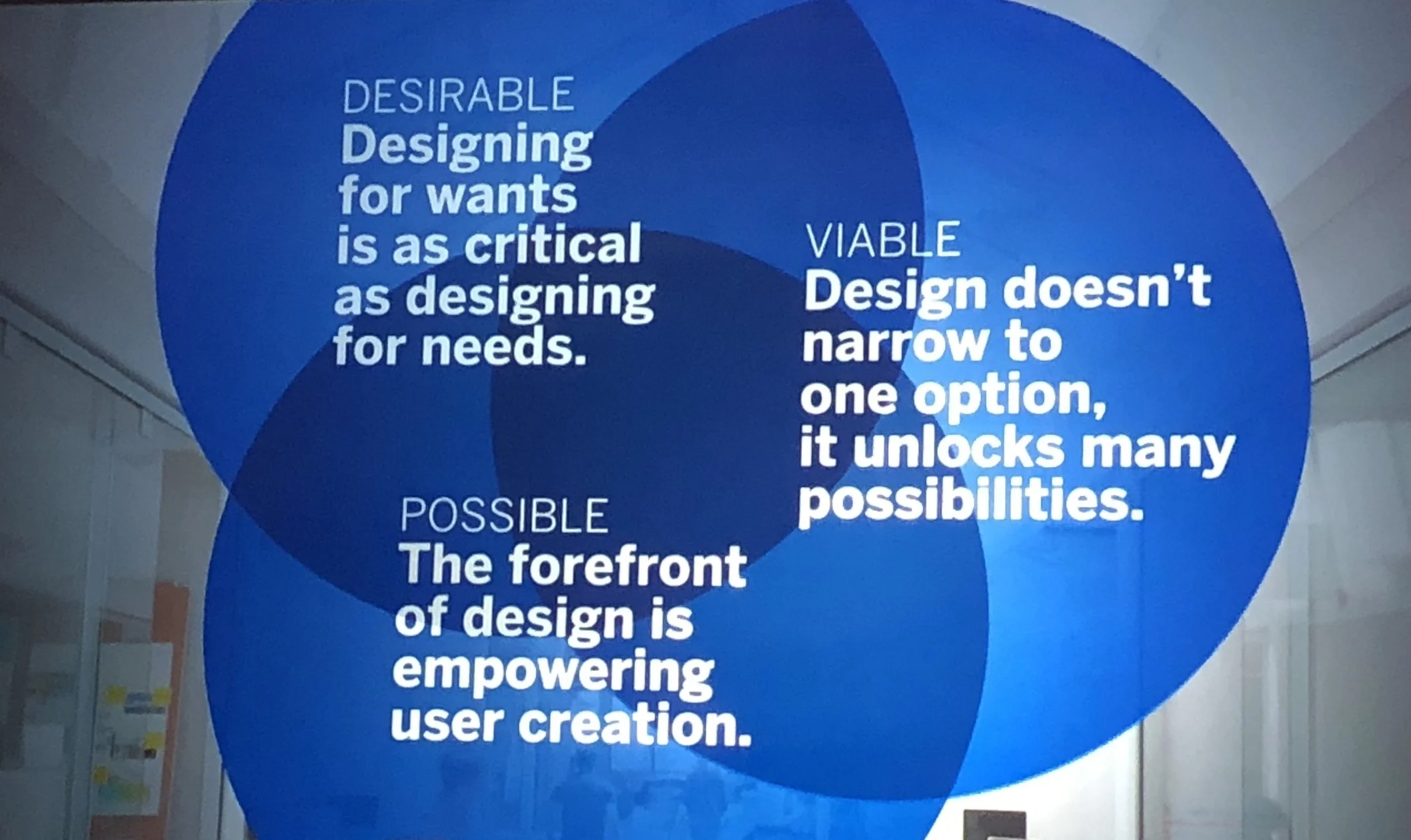

Credit: IA Collaborative

Finally, she posited that the best design is three things. Design should be desirable. “Designing for wants is as critical as designing for needs.” If a user doesn’t want to use a product, then they won’t use it even if they need to, and this can be a problem. For example, Brandenburg said that 40% of annual deaths from each of the five leading US causes were preventable. She learned about the lives of people with Type II diabetes and found that kids and adults are often reluctant to receive insulin because administration is tedious, inconvenient, and uncomfortable. Her team developed a simpler, more elegant system that people would want to use. Design should be viable. Designers should plan for the goal and not get stuck on the specific problem. According to the urban planner Fred Kent, “If you plan cities for cars and traffic, you get cars and traffic.” By going beyond the immediate problem, architects can understand the occupants’ lives and engage with the greater community. Finally, design should be possible, meaning that the best design empowers user creation.

3. Technology should enhance the human experience.

From smartphones to mixed reality to artificial intelligence, technology can profoundly shape the ways in which we, as consumers, live. As designers, there are consequences of the things that we do. Claude Zellweger (Google) explained that we should create the future we want to live. While technology can streamline interactions, making things more convenient can also sterilize insights. Sometimes friction and trying hard can be good. Further, he thinks that we should teach “digital hygiene” so that people learn to both engage and disengage with technology. Tech, if used well, can build real-life connection, empathy, intimacy, play, co-presence, and co-creation. The latter two are especially relevant to EDR’s use of virtual reality, which has the potential to enhance the dialogue between designers, clients, and the community. Tech like this should be pushed to augment communication, connection, and interaction, not only show projects in dazzling new ways.

4. Diversity and balance drive innovation.

Nichole Rouillac spoke about her experienced role of gender in the design discipline.

Balance in the design fields include personalities, work style, deadlines, etc. Nichole Rouillac (Level Design) delivered a powerful talk about another aspect of balance in design disciplines that every design workplace should consider: gender. She posited that diversity drives innovation and profitability. She wished she could leave out gender when describing herself as a designer, but she felt responsible to share her experiences and force an uncomfortable discussion to promote a more balanced industry. “We [as designers] are the change-makers.” The following discussion is from Rouillac’s perspective:

Historically in design, there is little room for women high up in the ranks. Women are also leaving for several reasons: unsupportive environments and culture, limited upward mobility and pay disparity, lack of voice and recognition, schedules and travel inflexibility, family impossibilities, and dissatisfaction in roles. Future female leaders should be relentless and believe in themselves, embrace their unique feminine selves, support and mentor women, and don’t give up. The industry should invest in women and empower women, advocate for and mentor, talk openly and honestly about these issues, set and commit to principles, and re-code behaviors and unconscious bias. The last recommendation is vital to changing the gender paradigm and culture of the current practice. Rouillac finished by explaining that “women need role models. Success compounds success.” She urged everyone to keep an open mind because everyone has a voice.

5. Design for existing human behaviors.

Some of the most effective design requires no adaptation to use it and can be appreciated by a diverse group. Coming from a background and working in interaction design, Christian Ervin (x the moonshot factory, Tellart) explained the impact of and opportunity with emerging tech on the way we live. How do we design in the 21st century? Ervin posited that the answer needs to account for the many diverse perspectives that exist in the target populations. Good futures are human-centered and inclusive, directed by cultural values and personal concerns, not technology itself. For example, one project he worked on transformed the idea of a routine physical in a cold doctor’s office into an interactive and immersive game that also happened to promote exercise, take body metrics, and replace a physical. In this way, an existing human behavior (gaming) directed a need (medical assessment) to become more of a want. Ervin and other speakers like Zellweger urged the audience to talk about the futures we want, cultivate an attitude of skeptical optimism, and collaborate between discipline

With the right vision, a doctor’s office visit could be transformed into an interactive, game-like experience. Image source: Tellart

6. Envision the future together.

As designers, it is normal for us to imagine what could be. “What if finding your parked car were easier?” A lot of the time, brainstorming is done alone in someone’s own head. When that person goes to others with the idea, the colleagues might be opposed to or at least not fully understanding of the idea or excitement in favor of their own current goals and pressing priorities. Pamela Bailey (Facebook) & Ricardo Marquez said that this stifles creativity and innovation. Instead of spending energy trying to convince others, bring them along to envision the future together. Bailey and Marquez used the metaphor of time travel to demonstrate a repeatable and relatable strategy for more effectively creating change as a team:

Diagnose organizational readiness and understand support for change.

Why do we want to innovate? Who wants us to? Are they committed?

Prep for the journey.

Define team roles, mission, and guidelines.

Time jump (together).

Listen to the future, break the context, and shift perspectives.

Gather artifacts, tell/capture stories.

Return to and transform the present.

Bring concepts to life with stories (inspiration) and prototypes.

Move to the future.

Make tangible insights happen.

As designers, we should not shy away from collaborative brainstorming and inspiration. In an open office, conversations and co-creation are especially accessible. So next time you sit down for a heavy thought session, skip over the catchup and convincing stage and bring your team along from the start to envision the future together.

7. Bend constraints to solve a problem.

Lloyd Cooper (PUSH) told the story of his father in World War II to demonstrate a point about bending constraints. When the hedgerows in Normandy prevented tanks from infiltrating German forces, Cooper’s father realized that leftover Hedgehogs (spikes on beach) could be modified and repurposed to be mounted onto the front of the tanks. This allowed the Americans to rip through the thick brush with ease and “won the battle.” We all work under constraints, and it is up to creative minds to gather potential resources and releverage what already exists to bend constraints and solve a problem.

8. The key to progress is celebration.

“Health is hard.” It involves not just eating, drinking, and exercise, but also sleep, connection, supportive and clean environments, and balance. To help people achieve a healthy lifestyle, Jonah Becker (Fitbit) said, designers should understand people and their activities; know the paths of least resistance. Especially salient was his explanation of achieving these kinds of goals. First, set a goal, and then make a realistic plan to achieve it and progress to the goal. The key to this progress is celebration. Micro-celebrations and feedback lead to good long term habits. So we shouldn’t hold back from complimenting our coworkers or teams along the way (not just after a project).

9. Work across disciplines and with the community.

Colleen McHugh (The Water Institute of the Gulf) spoke about sustainability and resiliency in coastal communities (i.e., New Orleans). Land is sinking, sea level is rising, and there is extreme rainfall and a rise in overnight temperatures. What role can design play in creating a more resilient community?

Translate the science. For a community with such diverse educational backgrounds and experiences, it is important to make important data and research findings accessible enough to really be appreciated. Websites like Ready for Rain have helped make issues of climate change more personal and actionable.

Design with nature. Learn from past change to make informed decisions in the future. Pair adaptation with community empathy.

Design for multiple benefits. Redesign can simultaneously lead to health, economic development, social cohesion, and education, which could be additional selling points.

Create a vision for the future. Promote a visible sense of optimism and a shared inspiration to enhance the community.

Design with communities. It is vital to for designers and other community members to understand each other through community engagement.

Make a lot of friends in other disciplines. With such a complicated issue, help from experts in other disciplines like earth sciences, chemistry, economics, and anthropology can be crucial.

One design decision can open up opportunities for many more. Image source: The Water Institute of the Gulf

Wilson W Smith III spoke about his shoe design work with diverse populations at Nike.

10. Design for Diversity

The conference ended with a bang. Wilson W Smith III exuded excitement, kindness, and passion for his work. As a shoe designer who has worked with world-class athletes like Michael Jordan, Andre Agassi, and Serena Williams, with disabled children, and with low-income indigenous communities, he designs for diversity and encourages embracing the unexpected. He made a case for “informed empathy” that requires truly understanding users and their lives. Spontaneously breaking out into a rap from Hamilton, he showed that a person’s circumstances shouldn’t hold them back from making an impact through design. Most of all, he proposed the role of mixing and improvisation: let people craft their own design stories.

Hearing about these speakers’ journeys and what they learned along the way was inspiring. As architects, we can borrow whatever realizations, strategies, and stories that might be useful in our own practice. Remember that architecture is made by people and for people. We should always consider the people we are designing for and the diverse perspectives and experiences they might have. Consider how a want might be a need, how our users behave and think, what resources we have and could have, and how we can bring refreshed excitement to the team, firm, and field.