Material Spotlight: Carpet

This blog post will trace how the widespread adoption of carpeting was facilitated through the invention of synthetic fibers and the disproportionate effects on workers and fenceline communities, a term that describes those who live near refineries or factories and experience the direct impacts of pollution. It will also examine how carpets and textiles are high risk materials for modern slavery and forced labor issues. The goal is to uncover how, as the Modern Slavery Index writes, “exploitation is by design, not default”[1] and ways designers can make change for a more just future.

How can modern slavery and systemic injustice be right under our feet? The truth is that our carpet and rug selections may be embedded in dubious supply chains.

When Looms Started to Weave Oil

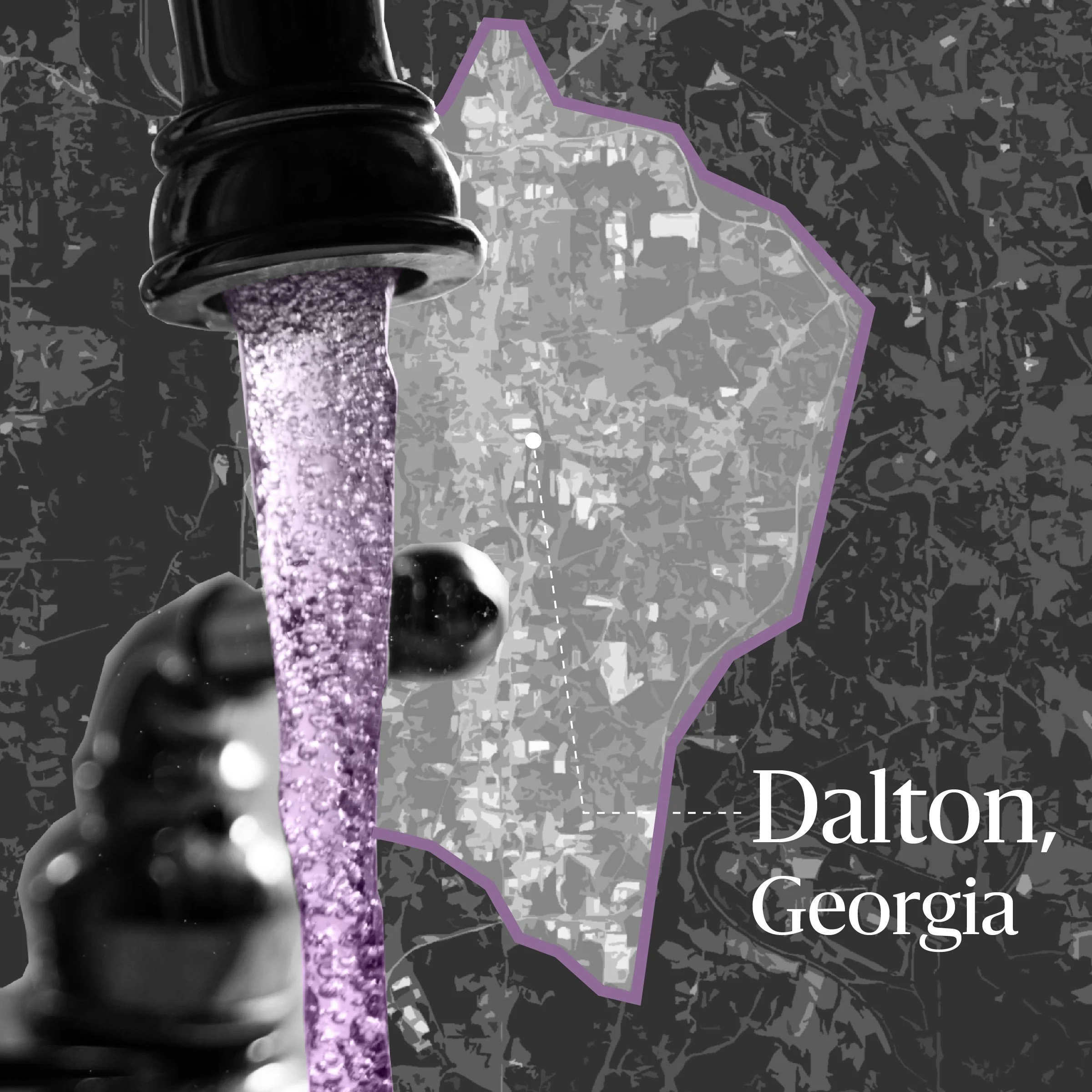

We often don’t realize that when we talk about commercial carpets, we are really talking about plastic. Without plastics, carpeting would have remained a luxury item that it had been throughout history. Even with the innovation of power looms in late 1830s America, carpets made from natural fibers like wool and silk were still not affordable for the average homeowner.[2] However, this all changed in Dalton, Georgia, when craft traditions were revived on an industrial scale - with plastic threads.

In the 1890s, the craft tradition of tufting, where a textile is created with loose fibers on the surface that are looped into a woven backing, was discovered.[3] As the fuzzy, soft textile resurged in popularity in the south, industry responded. By the 1950s, manufacturing capacities had grown to automate the tufting process at the scale of a floor covering for an entire room. And manufacturing in Georgia saw its opportunity.

Prior to the 1950s, the American commercial carpet industry focused on relatively expensive woven wool textiles and manufacturing was concentrated in the northeast. Georgia-based companies used the new mechanized tufting technique and regionally grown cotton fibers to offer carpets at a significantly lower price than their northern counterparts.[4]

Although customers favored the affordable option, these cotton carpets were notably poorer quality than wool, preventing any real challenge to the high-end side of the industry.

What changed to make carpeting the most sold flooring in the U.S.?[5] Plastic.

With the introduction of nylon, a type of plastic made from petrochemicals, the carpet industry had finally found a fiber with comparable performance to wool that could be vastly less expensive. An economic boom was born, making Dalton, Georgia the “Carpet Capital of the World.”

What’s in a Carpet?

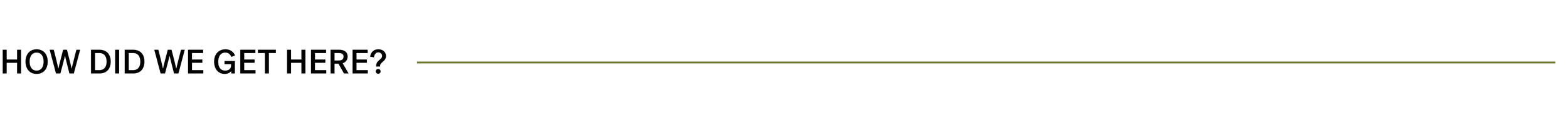

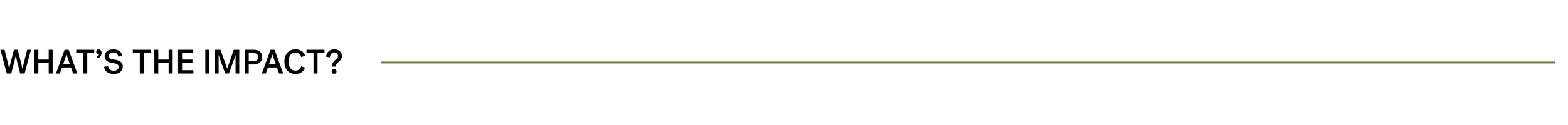

Commercial carpets today are composed of the following three elements: The pile, or the visible fibers, the backing, and protective surface treatments. The pile is often a type of synthetic fiber, like nylon, polyester or polypropylene, which are all derived from petroleum or fossil fuels.[6] Backings are most likely synthetic rubber, polyurethane, or PVC plastic.[7] Finally, carpets have historically been treated with perfluoroalkyl or polyfluoroalkyl substances, known as PFAS, to increase their stain-resistance performance.

Unfortunately, each of these three components are made from toxic chemicals that create social equity issues.

Worker Safety & Manufacturing

PFAS

Georgia, United States

Currently, the citizens of Rome, Georgia are suing multiple carpet manufacturers in Dalton, who still produce 75% of the global carpet supply,[8] for contaminating their water with PFAS.[9] Dubbed “forever chemicals,” PFAS have an exceptional ability to repel water and stains. In carpet manufacturing, PFAS chemicals were used to lubricate yarns to make them easier to weave[10] and as a surface treatment to protect the final product from stains.[11] Unfortunately, PFAS are also shown to cause serious health consequences, such as reproductive harm and increased risk of cancer, and will never break down naturally.[12]

In areas of manufacturing, the increased concentration of PFAS in waterways presents even greater health concerns to the affected communities.[13]

Located downriver of the carpet manufacturers, Rome implemented emergency filtration processes once the drinking water tested positive for dangerous levels of PFAS.[14] However, there is currently no way to remove PFAS from the human body once it has been exposed.

Responding to this, many carpet manufacturers are now phasing out PFAS surface treatments from their products.[15] However, chemical exposures during manufacturing are still a significant workers’ rights issue, especially considering the equity concerns in the carpet industry. In the 1980s and 1990s, this industry in Dalton was facing a labor shortage, and found a solution in hiring Hispanic workers, many of whom were undocumented immigrants.[16] Randall Patton, Professor of History at Kennesaw State University and Shaw Industries Distinguished Chair, states that this had very positive outcomes, explaining that the industry trailblazed globalization and support of the culture and needs of workers in the Dalton community.[17] Still, many workers and their families were exposed to these toxic chemicals at high levels and without any disclosure, while labor costs were kept low.

Unfortunately, when it comes to carpets, this is not the only environmental justice concern.

Fenceline Communities

Synthetic Rubber

“Cancer Alley”

Louisiana, United States

Between Baton Rouge and New Orleans, Louisiana, the ongoing effects of systemic racism are seen through the environmental injustice faced by fenceline communities.

In November 2024, Fifth Ward Elementary School, located in the predominately Black community of St. John the Baptist Parish, was voted to be closed.[18] For years prior, over 300 children ranging from pre-kindergarten through fourth grade went to class less than one mile away from Denka Performance Elastomers LLC, a plant which produces the synthetic rubber commonly known by the tradename Neoprene.

Neoprene is used to make wetsuits, window seals and other common products. Synthetic rubber is often used in carpet backings and padding.[19]

The issue is that the Denka plant releases chloroprene, the essential chemical needed to make Neoprene, into the air at high concentrations.[20] In 2010, the EPA named chloroprene a likely carcinogen.[21]

Adrienne Katner, an environmental health professor at Louisiana State University, expands that chloroprene is a known mutagen, which means it alters DNA, leading to cancer and “irreparable damage to organs.”[22] While everyone exposed is at risk, children are most in danger: “Children are growing very fast. Their cells are dividing. As their cells divide, that DNA is exposed, so this is a critical period.”[23]

According to a motion filed by the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, the school board was in violation of a “desegregation order by disproportionately exposing Black students to Denka’s pollution when there are alternative schools they could attend elsewhere in the district and in many cases closer to their homes.”[24] However, the decision to close the school hurts the residents of St. John the Baptist in other ways. Parents and teachers shared during public hearings with the school board how painful this solution was because it would separate the close community of the school.[25]

Concerns were also raised that the closing of Fifth Ward Elementary School ultimately does little to protect the children’s health. Raydel Morris, a member of the school board representing the Fifth Ward neighborhood, expressed that “the board’s proposed solution would fail to meaningfully end most students’ exposure to Denka’s pollution by moving many to another school, East St. John Preparatory, less than 1 mile from the facility.”[26]

This story is only one of many in the region between Baton Rouge and New Orleans, Louisiana, aptly called “Cancer Alley,” where factories and refineries along the Mississippi River emit a range of chemicals that harm historically Black communities with toxic emissions.[27]

In response to health consequences of chloroprene pollution and its disproportionate impacts on minority communities, there are several actionable steps to consider.

Regulation:

While chloroprene is an essential ingredient in Neoprene, stronger regulation around acceptable emission levels will help to protect the fenceline communities surrounding the manufacturing plants. A rule issued by the EPA on April 9, 2024 intends to “reduce both EtO and chloroprene emissions from covered processes and equipment by nearly 80%” and require fenceline monitoring that would be public data.[28] This strategy of harm reduction is an important step in protecting the people living in Cancer Alley.

Substitutions:

As designers, we can opt for carpet backings that do not require the production of synthetic rubber. There are a growing number of backing options that are made of recycled or biobased content. One example is the CQuestBio backing from Interface.

Natural Rubber:

Alternatively, natural rubber avoids this issue of harmful pollution but does present another equity risk of potentially being sourced through forced labor. Design For Freedom expands on this in their Toolkit, where they also provide certifications that can verify ethical practices in the extraction of latex used in rubber. The certifications to look for include PEFC Certification for Rubber Growers, Fairly Traded Natural Rubber, and FSC Certified products.

Importantly, synthetic rubber is just one product that impacts those in Louisiana’s “Cancer Alley.” Also produced in the factories is the chemical chlorine for PVC plastic, used as another common carpet backing option. Yet another environmental justice issue, the process to manufacture chlorine in the U.S. relies on asbestos, which is also harmful to human health and was recently banned by the EPA. Manufacturing materials with asbestos harms those working to mine the hazardous mineral and the communities surrounding the plants.[29]

Forced Labor & Modern Slavery

PVC

Uyghur Region, China

However, China is currently the world’s largest manufacturer of PVC, with direct ties to the forced labor of the Uyghur people.

Two plants located in the Uyghur Autonomous Region of China produce 10% of the world’s PVC supply: Xinjiang Zhongtai Chemical (2.33 million tons per year) and Xinjiang Tianye (1.4 million tons capacity per year)[30]

The Uyghur people are a minority group within China. They have faced suppression of their Turkic language and Muslim practices, with worsening persecution since the early 2000s.

Allegedly to offer poverty relief and vocational training, “re-education camps” are run throughout the Uyghur Region. However, according to US Secretary of State, Antony Blinken, this is genocide.[31]

“State-imposed forced labour reportedly occurs alongside political indoctrination, religious oppression, mass surveillance, forced separation of families, forced sterilisation, sexual violence, and arbitrary detention in so-called ‘re-education camps’ within the Uyghur region.”[32]

These camps, which are an attempt to eradicate the culture of the Uyghur people, are an example of modern slavery, as those inside are not permitted to leave and are not fairly paid for their labor. Modern slavery is defined by Anti-Slavery International as occurring “when an individual is exploited by others, for personal or commercial gain. Whether tricked, coerced, or forced, they lose their freedom. This includes but is not limited to human trafficking, forced labor and debt bondage.” As PVC is in widespread use within our construction industry, in carpet, window frames, and pipes, there is the risk that these products may be linked to the suffering of those forced to produce it.

Natural fiber and Hand-woven Alternatives

Unfortunately, it is not so simple to avoid the equity issues in carpet manufacturing by opting for natural materials. The problem is that the textile industry has long been associated with forced and child labor.

In 2014, Siddharth Kara published a report through the Harvard School of Public Health, identifying that most Indian hand-made carpets are produced through child labor.[33] According to the U.S. Department of Labor in 2022, textiles from Pakistan, Vietnam and Ethiopia are also at risk of child labor in their production.[34]

According to the U.S. Department of Labor, forced and child labor also occurs in the processing of natural fibers, such as jute and cotton, in multiple countries.[35] It is an unfortunate reality that a natural material may be tied to supply chains that are equally as unjust as its synthetic counterparts and underscores the insidious nature of modern slavery. Ultimately, modern slavery is interwoven with all our supply chains in more ways than we even currently know, with textiles and carpets often at the highest risk.

According to the Global Slavery Index 2023 report:

“Modern slavery permeates every aspect of our society. It is woven through our clothes, lights up our electronics, and seasons our food. At its core, modern slavery is a manifestation of extreme inequality. It is a mirror held to power, reflecting who in any given society has it and who does not. Nowhere is this paradox more present than in our global economy through transnational supply chains.”[36]

Policy and Building Industry Reform

In 2022, the United States Government enacted the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA), which bans the importation of products manufactured in the Uyghur Region. The law authorizes a task force to ensure the enforcement of this ban, considering both products and materials. In 2024, this task force added PVC as a priority material in screening for modern slavery practices in manufacturing.[37] While the official reports are encouraging, citing that the policy and task force have been successful in significantly reducing forced labor in U.S. supply chains, concerns arise that these camps have migrated to other regions of China and export products made with forced labor under the radar of the task force.[38]

However, federal initiatives to protect those living in Louisiana’s “Cancer Alley” have recently experienced notable setbacks. In 2022, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) launched an investigation into alleged violations of the Civil Rights Act by the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality in allowing the severity of pollution in the region. However, the EPA dropped the investigation in 2024, after a lawsuit from then attorney general and now state governor, Jeff Laundry, was launched against the agency.

Some reports speculated that the decision to drop the case was motivated by concerns that the EPA might lose the lawsuit and potentially its authority to investigate racial discrimination issues more broadly. According to reporter Delaney Nolan, “Five weeks after Landry filed his suit, the EPA dropped its investigation, effectively leaving Cancer Alley residents to continue the struggle on their own.”[39]

How Designers Can Make Change

It’s sobering to think that one square of carpet tile could be systemically harming people in Georgia, Louisiana, and Xinjiang, China. The problem is not just carpet, it’s plastic. Plastics are used in almost everything, from vinyl flooring to food storage containers.

According to Indigenous rights and environmental justice activist Winona LaDuke, the struggle is much deeper than simply where these plants and pipelines are built.[40] The fault lines are along our societal issues of discrimination and injustice, but the core issue is plastic and our apparent inability to live without it. Winona LaDuke states, “We’re all fossil fuel addicts.”[41] LaDuke explains she uses this metaphor to question why we keep insisting on needing plastics and petrochemicals when we know how much harm they are causing to others. The 2023 Global Slavery Index states, “If there is one message you should take from this Index, it is that exploitation is by design, not default.”[42]

However, we also must recognize that our insistent use of making things with plastic explains why carpet manufacturers started to favor synthetic materials over natural ones nearly a century ago. Plastics are cheaper than natural materials and perform as well or even better. How can designers reconcile this apparent conflict in our standard of care?

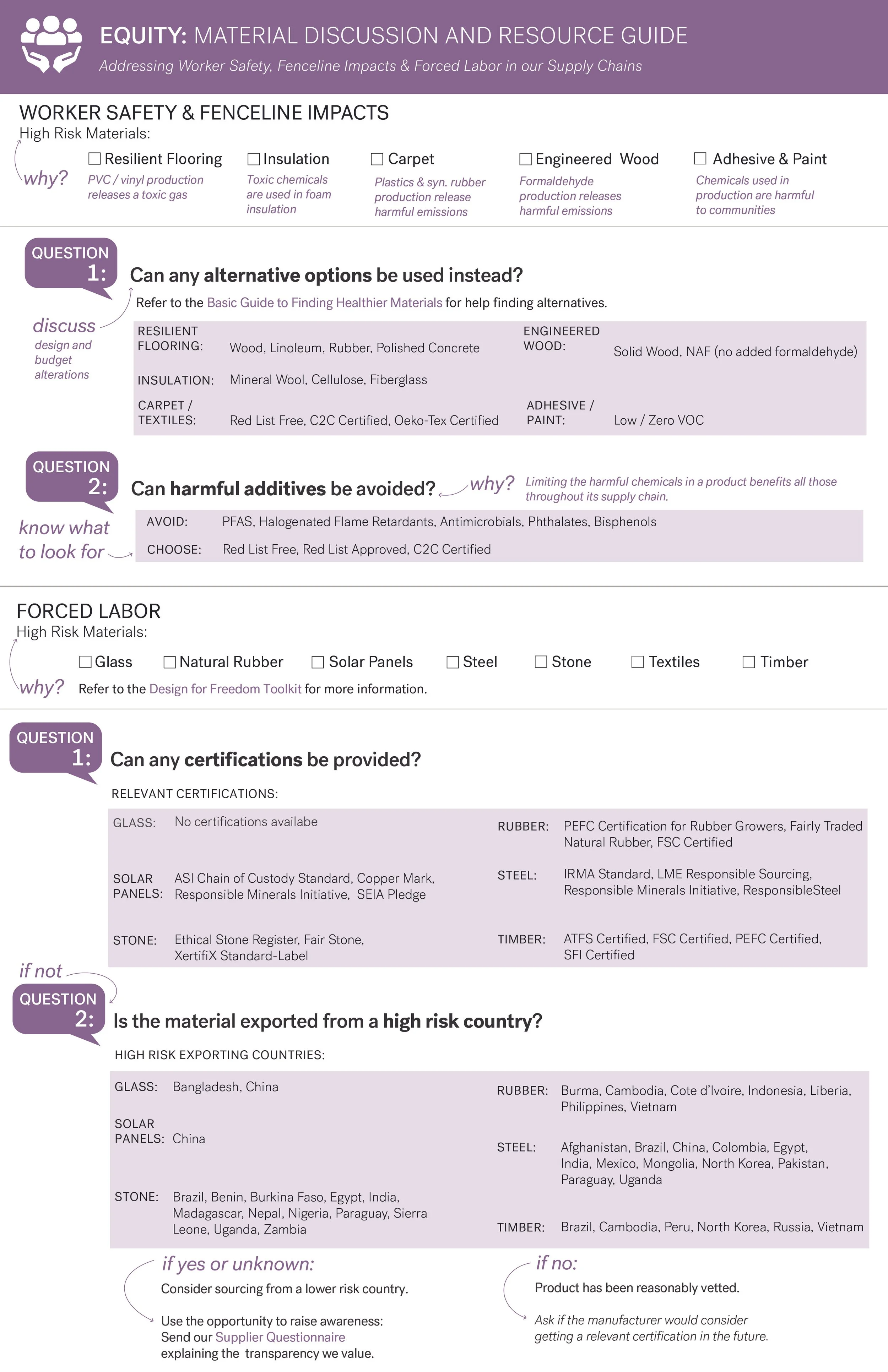

Ask Questions:

Ask product reps and vendors where the materials are sourced from and how they are manufactured. This may reveal insights into fenceline issues or open questions about labor practices. By asking, we can signal to manufacturers that these issues are important to us and can help teams make more informed choices.

For help with this step, Design For Freedom as a standardized Supplier Questionnaire that can be sent to reps.

In cases where you feel most of this information will be unknown, we have developed a simplified version of the questionnaire to lower the barrier to entry and start these conversations:

Think holistically:

The problem of petrochemicals and PFAS are also recognized as human health issues, in addition to understanding them on an environmental justice level. Specifying healthier materials without chemicals of concern helps ensure that workers and fenceline communities are protected as well. Certifications like Cradle to Cradle address issues of social equity and material health together.[43]

Prioritize Materials:

Modern slavery is widespread throughout global supply chains, but we must begin our action somewhere. Look into the materials you use the most of. What do the supply chains look like? If there are alternatives that provide transparency around their sourcing and manufacturing, can you switch to those instead?

The most important thing we can do surrounding equity issues is to keep talking about them. However, it can be difficult to start and guide a discussion about which materials to focus on and what impact they have. To help with this, we have developed a discussion and resource guide that prompts focused questions and includes the information necessary to know what to research further.

Consider continuing this discussion in your teams with the support of this resource:

Works Cited

[1] “The Global Slavery Index 2023,” Walk Free, November 3, 2023, https://www.walkfree.org/global-slavery-index/.

[2] Randall Patton, “Carpet Industry,” New Georgia Encyclopedia, October 6, 2019, https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/business-economy/carpet-industry/.

[3] “The History of Carpet: Carpet One Floor & Home,” Carpet One, May 3, 2022, https://www.carpetone.com/blog/history-of-carpet.

[4] Randall Patton, “Carpet Industry,” New Georgia Encyclopedia, October 6, 2019, https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/business-economy/carpet-industry/.

[5] Jim Vallette, Rebecca Stamm, and Tom Lent, “Eliminating Toxics in Carpet: Lessons for the Future of Recycling,” Habitable, October 2017, https://habitablefuture.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/81-eliminating-toxics-in-carpet-lessons-for-the-future-of-recycling.pdf.

[6] “The Pros and Cons of Natural and Synthetic Carpet: Springer,” Springer Floor care, May 26, 2023, https://springerfloorcare.com/the-pros-and-cons-of-natural-and-synthetic-carpet/.

[7] Kathy Long, “3 Common Commercial Carpet Backing Types,” 3 Common Commercial Carpet Backing Types, August 6, 2020, https://blog.manningtoncommercial.com/3-common-commercial-carpet-backing-types.

[8] “Dalton, Georgia: Carpet Capital of America,” Georgia Public Broadcasting, accessed December 4, 2024, https://www.gpb.org/georgiastories/stories/tufted_bedspread_industry#:~:text=Today%2C%2075%25%20of%20the%20world’s,Bedspread%20Alley%20on%20Highway%2041.

[9] Megan Butler, “Panel Asked to Hold Georgia’s ‘carpet Capital’ Liable for Contaminated Drinking Water,” Courthouse News Service, September 13, 2022, https://www.courthousenews.com/panel-asked-to-hold-georgias-carpet-capital-liable-for-contaminated-drinking-water/.

[10] Maya Gilchrist, “Pfas in the Textile and Leather Industries,” Minnesota Pollution Control Agency, May 2023, https://www.pca.state.mn.us/sites/default/files/gp3-06.pdf.

[11] “Chemicals: Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl (PFAS) Substances,” Wisconsin Department of Health Services, April 10, 2024, https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/chemical/pfas.htm.

[12] “Our Current Understanding of the Human Health and Environmental Risks of PFAS,” EPA, November 26, 2024, https://www.epa.gov/pfas/our-current-understanding-human-health-and-environmental-risks-pfas.

[13] Bloomberg Investigates, “The Forever Chemical Scandal,” Bloomberg Originals, November 8, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t8qGtEVh7oQ.

[14] Megan Butler, “Panel Asked to Hold Georgia’s ‘carpet Capital’ Liable for Contaminated Drinking Water.”

[15] “Study: PFAS in Carpets a Major Exposure Source for Children,” Green Science Policy Institute, April 29, 2020, https://greensciencepolicy.org/news-events/press-releases/study-pfas-in-carpets-a-major-exposure-source-for-children#:~:text=Most%20carpet%20manufacturers%20recently%20stopped,stain%2D%20and%20soil%2Dresistant.

[16] Randall Patton, “Carpet Industry,” New Georgia Encyclopedia, October 6, 2019, https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/business-economy/carpet-industry/.

[17] Randall Patton, “Carpet Industry,” New Georgia Encyclopedia.

[18] Jack Brook, “Majority Black Louisiana Elementary School to Shut down amid Lawsuits over Toxic Air Exposure,” AP News, November 9, 2024, https://apnews.com/article/denka-elementary-school-5th-ward-cancer-alley-d8c1307c780f7c457b745f16cf042450.

[19]Jim Vallette, Rebecca Stamm, and Tom Lent, “Eliminating Toxics in Carpet: Lessons for the Future of Recycling,” Habitable, October 2017, https://habitablefuture.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/81-eliminating-toxics-in-carpet-lessons-for-the-future-of-recycling.pdf.

[20] Jack Brook, “Majority Black Louisiana Elementary School to Shut down amid Lawsuits over Toxic Air Exposure,” AP News, November 9, 2024, https://apnews.com/article/denka-elementary-school-5th-ward-cancer-alley-d8c1307c780f7c457b745f16cf042450.

[21] “Toxicological Review of Chloroprene,” EPA, September 2010, https://iris.epa.gov/static/pdfs/1021tr.pdf.

[22] Halle Parker, “Lawyers Push to Relocate St. John Elementary Students from School next to Chemical Plant,” Louisiana Illuminator, July 18, 2024, https://lailluminator.com/2024/07/18/school-chemical-plant/.

[23] Halle Parker, “Lawyers Push to Relocate St. John Elementary Students from School next to Chemical Plant.”

[24] Jack Brook, “Majority Black Louisiana Elementary School to Shut down amid Lawsuits over Toxic Air Exposure,” AP News, November 9, 2024, https://apnews.com/article/denka-elementary-school-5th-ward-cancer-alley-d8c1307c780f7c457b745f16cf042450.

[25] Jack Brook, “Majority Black Louisiana Elementary School to Shut down amid Lawsuits over Toxic Air Exposure.”

[26] Jack Brook, Ibid.

[27] Delaney Nolan, “The EPA Is Backing down from Environmental Justice Cases Nationwide,” The Intercept, February 2, 2024, https://theintercept.com/2024/01/19/epa-environmental-justice-lawsuits/.

[28] EPA Press Office, “Biden-Harris Administration Finalizes Stronger Clean Air Standards for Chemical Plants, Lowering Cancer Risk and Advancing Environmental Justice,” EPA, April 9, 2024, https://www.epa.gov/newsreleases/biden-harris-administration-finalizes-stronger-clean-air-standards-chemical-plants#:~:text=%E2%80%9CToday%20marks%20a%20victory%20in,chemicals%20including%20EtO%20and%20chloroprene.

[29] Jim Vallette, Rebecca Stamm, and Tom Lent, “Eliminating Toxics in Carpet: Lessons for the Future of Recycling,” Habitable, October 2017, https://habitablefuture.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/81-eliminating-toxics-in-carpet-lessons-for-the-future-of-recycling.pdf.

[30] Laura T. Murphy, Jim Vallette, and Nyrola Elimä, “Built on Repression: PVC Building Materials’ Reliance on Labor and Environmental Abuses in the Uyghur Region,” Human Trafficking Search, 2022, https://humantraffickingsearch.org/resource/built-on-repression-pvc-building-materials-reliance-on-labor-and-environmental-abuses-in-the-uyghur-region/.

[31] “Who Are the Uyghurs and Why Is China Being Accused of Genocide?,” BBC News, May 24, 2022, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-22278037.

[32] “The Global Slavery Index 2023,” Walk Free, November 3, 2023, https://www.walkfree.org/global-slavery-index/.

[33] Siddharth Kara, “Tainted Carpets: Slavery and Child Labor in India’s Hand-Made Carpet Sector,” FXB Center for Health and Human Rights, 2014, https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/2464/2020/01/Tainted-Carpets-Released-01-28-14.pdf.

[34] Office of Child Labor, Forced Labor, and Human Trafficking, “List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor,” DOL, September 2022, https://www.dol.gov/agencies/ilab/reports/child-labor/list-of-goods.

[35] Office of Child Labor, Forced Labor, and Human Trafficking, “List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor.”

[36] “The Global Slavery Index 2023,” Walk Free, November 3, 2023, https://www.walkfree.org/global-slavery-index/.

[37] “Forced Labor Enforcement Task Force Adds Aluminum, PVC, and Seafood as New High Priority Sectors for Enforcement of Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act: Homeland Security,” U.S. Department of Homeland Security, July 9, 2024, https://www.dhs.gov/news/2024/07/09/forced-labor-enforcement-task-force-adds-aluminum-pvc-and-seafood-new-high-priority.

[38] “Fact Sheet: In Just Two Years, Forced Labor Enforcement Task Force and the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act Have Significantly Enhanced Our Ability to Keep Forced Labor out of U.S. Supply Chains: Homeland Security,” U.S. Department of Homeland Security, July 9, 2024, https://www.dhs.gov/news/2024/07/09/fact-sheet-just-two-years-forced-labor-enforcement-task-force-and-uyghur-forced.

[39] Delaney Nolan, “The EPA Is Backing down from Environmental Justice Cases Nationwide,” The Intercept, February 2, 2024, https://theintercept.com/2024/01/19/epa-environmental-justice-lawsuits/.

[40] Winona LaDuke, “Winona LaDuke Keynote Address: Material Health: Design Frontiers,” Healthy Materials Lab, November 14, 2019, https://healthymaterialslab.org/learning-hub/winona-laduke-keynote-address-at-material-health-design-frontiers.

[41] Winona LaDuke, “Winona LaDuke Keynote Address: Material Health: Design Frontiers.”

[42] “The Global Slavery Index 2023,” Walk Free, November 3, 2023, https://www.walkfree.org/global-slavery-index/.

[43] “Cradle to Cradle Certified®,” Cradle to Cradle Certified® - Cradle to Cradle Products Innovation Institute, accessed September 4, 2024, https://c2ccertified.org/the-standard.