LEED v5: Please Mind the People in the Margins

As designers, we know that sustainability is about more than just energy and water; it’s about people. The USGBC’s latest LEED v5 reflects a meaningful shift in how our industry defines sustainable design, emphasizing not just environmental performance but human and social impact. A central part of this shift is the new IP Prerequisite: Human Impact Assessment, which requires teams to look closely at how projects affect communities, especially those historically pushed to the margins. In this piece, Aida Ayuk explores what it means to truly design with equity in mind and how frameworks like LEED v5, the Just | Change Fellowship, and tools like the Equity Guide and "Mapping Equity" Resource Book can help designers see, and shift, the boundaries that shape our built environment.

Margins exist for a reason.

They hold the space between what’s valued and what’s ignored. In typography, margins frame content, providing space for annotations and corrections. In our cities, they keep things tidy by hiding what makes us uncomfortable.

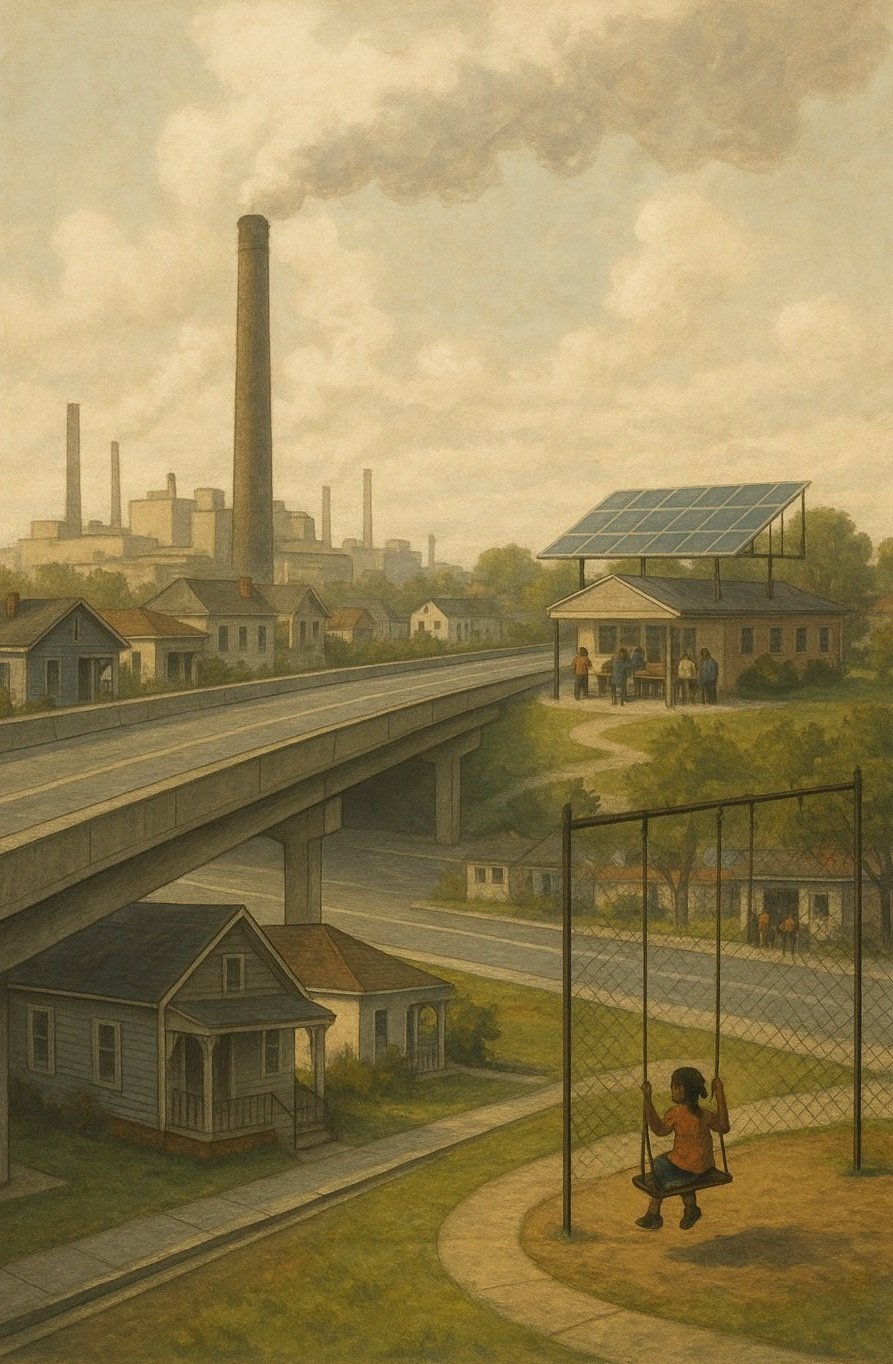

Margins represent where our collective decisions accumulate. They are the places where highways cut through Black neighborhoods in the name of progress, where power plants are located next to low-income housing, and where zoning and lending practices redraw the edges of belonging. These boundaries are not incidental. They are the product of generations of policy and design. Often justified as buffers between industry and homes, or risk and investment, these spaces reveal the deep fault lines in our built environment. They separate clean air from toxic exposure, mobility from confinement, and opportunity from exclusion. To understand human impact, we must recognize that these margins are not neutral. They are intentional human landscapes, shaped by historical forces that continue to affect communities today.

And LEED v5 is finally asking us: Have you been paying attention to what’s in your margins?

The Evolution of LEED Towards Equity

LEED has evolved beyond environmental performance to embrace human and social impacts, reflecting broader shifts in societal values. LEED v5 is organized around three core impact areas, one of which, Quality of Life, centers well-being, resilience, equity, inclusion, and community health. With 25% of total points now dedicated to this area, LEED signals a stronger commitment to people-first design.

Several existing, updated, and new pieces in LEED v5 reinforce this shift. The new IP Prerequisite: Human Impact Assessment requires project teams to evaluate equity considerations from the outset. Building on this foundation, credits such as IP: Worker Safety and Training support social equity for operations and maintenance staff through safety planning and workforce development. LT: Equitable Development encourages investment in historically underresourced areas, promoting cultural, economic, and community health. SS: Heat Island Reduction addresses the unequal impacts of extreme heat on vulnerable populations. MR: Product Selection and Procurement rewards the use of materials with transparent, socially and environmentally responsible sourcing. Finally, EQ: Accessibility and Inclusion promotes inclusive design that meets diverse needs and fosters a sense of belonging for all occupants.

LEED v5’s Human Impact Assessment

In LEED v5, the IP Prerequisite: Human Impact Assessment emphasizes that real change begins with the ability to look, ask, and listen with intention.

The word margin comes from the Latin margo, meaning edge, border, or boundary, and in many ways, we are all living within these. Like the notes and edits in the margins of a page, our lived environments are shaped by layers of decisions that reflect histories of systemic neglect and inequality.

To meet this new prerequisite, project teams must complete an assessment that draws on relevant information from four specified categories, as applicable:

Demographics: “This may include race and ethnicity, gender, age, income, employment rate, population density, education levels, household types, and identification of nearby vulnerable populations.”

The people living in the margins are rarely there by choice. These boundaries often map directly onto race, income, and age, communities pushed out by policy, not pulled in by opportunity. Redlining, exclusionary zoning, and disinvestment have drawn lines around who gets clean air, quiet nights, and safe streets.Local Infrastructure and Land Use: “This may include adjacent transportation and pedestrian infrastructure, adjacent diverse uses, relevant local or regional sustainability goals/commitments, and applicable accessibility codes.”

At the margins, land use tells a familiar story: highways through Black neighborhoods called “progress,” power plants sited near low-income housing called “necessary.” Infrastructure choices aren't neutral, they’re a legacy of who was considered worth investing in.Human Use and Health Impacts: “This may include housing affordability and availability, availability of social services (e.g., healthcare, education, and social support networks), community safety and local community groups, and supply chain and construction workforce protections.”

These design decisions carry weight. Marginalized communities often face higher exposure to pollution, heat, noise, and unsafe streets. The built environment becomes a public health issue, with limited mobility, increased asthma, chronic stress, and fewer safe spaces to gather, play, or heal.Occupant Experience: “This may include an opportunity for daylight, views, and operable windows; environmental conditions of air and water; and adjacent soundscapes, lighting, and wind patterns within the context of the surrounding buildings (e.g., a microclimate, a solar scape, neighboring structures).”

Every edge, border, boundary shape how people live, feel, and what they expect from their environment. Less sunlight, more noise, fewer trees, all affect influencing everything from mental health to neighborhood identity. When ignored, entire communities are overlooked.

In short: understand the people, place, and history that you are designing for, and be accountable for your impact. So, how do we achieve this?

Just | Change: A Framework for Equitable Design

The Equity Guide and Mapping Equity: The Resource Book, developed as part of our 2023-2024 Just | Change Research Fellowship, help project teams conduct an equity-based site assessment. These tools recognize that the prosperity of this nation was built on the backs of displacement and enslavement, acts of violence that required systems of denial to justify them. These mental structures still endure today, reflected in a world where marginalized communities disproportionately bear the weight of pollution, climate change, and disinvestment.

The Equity Guide offers a structured framework of six EQUITY categories (Environmental Impact, Quantity of People, Unmet Community Needs, Intersectionality, Target Area Vulnerabilities, and Yes to Engagement) that help project teams identify and organize risks and opportunities, ensuring that the social and historical context of a place is not lost in the design process. Without equity, sustainability efforts risk becoming "gentrified greenwash," where surface-level solutions mask the deeper systemic issues.

The Mapping Equity Resource Book goes further. Each chapter invites us to look at a place from multiple perspectives, weaving together Narratives (stories from local stakeholders), Deep Dives (data and history), Spatial Mapping (visualizing equity patterns), and Case Studies (real-world examples). These layers form a mosaic of understanding, allowing us to see the nuanced, lived experiences of communities and respond.

This is only the start. Movements like Design for Freedom urge us to confront the human cost embedded in materials and labor. WELL’s Equity Rating, along with WELL v2’s beta credits for neurodivergent inclusion and supply chains, broadens our understanding of health, dignity, and equity in the built environment. Meanwhile, the AIA’s Framework for Design Excellence challenges us to design with equitable communities in mind.

Final Note

Addressing the “margins” requires a holistic approach, considering historical context, current realities, and future implications. LEED v5’s Human Impact Assessment serves as a catalyst for projects to move toward more equitable development. Your site has margins. Your team has blind spots. Your project has choices. It’s our responsibility to ensure our work doesn’t perpetuate marginalization but contributes to empowerment and well-being.