Building in our Time & Place - Part 1

There have been several articles in the last week about a recently released study, The future intensification of hourly precipitation extremes, that models the percentage increase in extreme downpours that will impact the United States in the future. The study indicates that these events, similar to the one that caused catastrophic flooding in Louisiana this summer, will occur five to six times more frequently in the Gulf South. This new research got me thinking about an event I attend several months ago.

During their weekly FIKA (coffee and conversation), The Blue House hosted a discussion about this summer’s flooding with; Mat Sanders - Louisiana Office of Community Development, Kyle Galloway - National Guard and GAEA Consultants, Jesse Hardman – Reporter, Grasshopper Mendoza and Steve Picou - Louisiana Water Economy Network, Dana Brown - Dana Brown & Associates, Lacy Strohschein - Greater New Orleans, Inc., Nathan Lott - Greater New Orleans Water Collaborative, Allison DeJong – Propeller, and Aron Chang - Waggonner & Ball Architects.

The discourse was framed around a series of questions posed and responded to by the invited guests. A few of the questions were of particularly interest to me in my position as a Research Fellow focused on issues of landscape architecture and urban systems. The first question - what could we have done different - grapples with an issue many people are struggling with in regard to city building and one that we need to understand in order to create innovative solutions to our biggest challenges.

What would the effect of the storm event have been if land use patterns looked different?

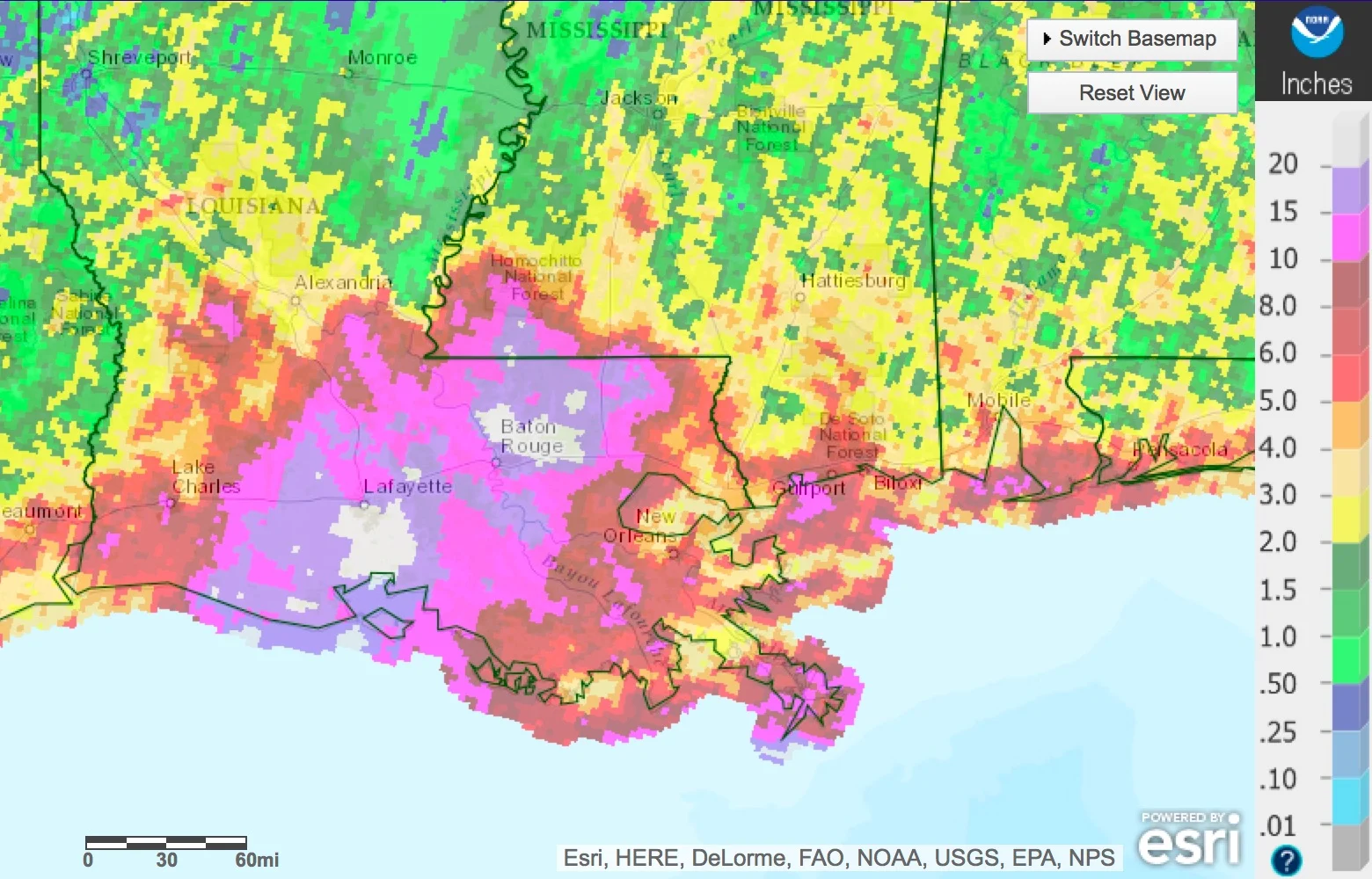

Rainfall totals during the storm.

To start to digest this question we need to try to comprehend the scale of this unnamed storm– 31.39” (6.9 trillion gallons) of water in the hardest hit area in under a week. This is more water than areas of California have received in 3 years and to put it in the context of New Orleans, it is the equivalent of the average flow of the Mississippi River for 18 days (388 billion gallons per day).

For an event of this size the ecological systems in the area can’t effectively manage the rainfall. The ground can’t soak up and infiltrate the water because the soils can only handle 2 – 3” of rain before they are saturated - the storm totaled over 10x that amount. So what could we have done differently to prevent the loss of life, property damage, and disruption to daily life that occurred? An article in The Times-Picayune on September 23 laid out several of these “what ifs” for land use, construction methods, and development practices.

“Most of the houses damaged in the Louisiana Flood of 2016 did not carry flood insurance because they were located outside FEMA's high-risk zone. And instead of limiting development, the flood insurance program has opened the door for more expensive homes, constructed on concrete slabs, to be built in areas likely to flood.”

We must take into account that this was not a named tropical storm with severe forecast impacts, that flooding occurred well outside of established FEMA flood zones, and that conventional development in the region continues to encroach on critical areas. Several question from the discussion follow up on this and push us to challenge the status quo of growth focused development. One of the most pointed of these was; we are learning new lessons every day, what are the barriers to implementing change using the information that we learn?

The conversation focused on how we must challenge the ways that information is disseminated and the decision making processes that result in our current conditions – from lengthy municipal master planning process to building design and material use, all directly tied to current political and economic systems. These systems, which operate on a model of investment and short term returns, do not incorporate considerations for potential loses and the benefits of building and development practices that can mitigated future disasters today.

One panelist stated that - with the knowledge that there are fewer and fewer resources available for recovery after every event we must work proactively to implement new development and recovery practices if we are going to effectively and justly rebuild. Under these conditions how can design and policy respond in more appropriate ways after a disaster? How can we find ways to rebuild that can mitigate future disasters and that value new development in ways beyond short term returns?

This new research about the increased frequency of extreme events presents a compelling case for finding new ways to plan and to build. We must create planning, design, financing, and construction processes that respond to an ever changing world and use the latest science to create innovative and timely projects.