Redesigning the Bruce for a Modern Audience | Part I - Creating an Institutional Vision

This is Part I of a four-part series recapping a recent presentation given at Building Museums 2020 that explores the nearly ten years of collaboration renovating and expanding the Bruce Museum.

Introduction

While EDR has always practiced broadly, throughout our thirty-year history the firm has simultaneously compiled a significant portfolio of work in the civic and cultural realm. In 2012, we were fortunate enough to win via design competition the opportunity to expand and renovate the Bruce Museum, a regionally based, world-class museum located in Greenwich Connecticut that brings art, science and natural history together under one roof.

As we begin to enter Phase II of construction, and the expansion of the new wing, we had the privilege to share some lessons learned last month at the recent Mid-Atlantic Conference of Museum’s “Building Museums” Symposium in Chicago.

There, Steve, along with Reed Kroloff (who managed and led the design competition soliciting architects via his firm jones|kroloff) and Bruce Director of Exhibitions Anne von Stuelpnagel were able to look back on our nearly ten year journey together via a presentation intended to share some of the following:

An effective and efficient process for hiring an architect for museum design

How a museum’s landscape can inspire the design and reinforce an institution’s mission

How a rigorous programming and planning phase can create a more compelling experience

How museum directors can best partner with architects in a collaborative process tailored to realizing a transformative vision for their institution

Following is a brief summary of the presentation given there—a case study in how a unified team navigated a complex set of concerns, programmatic issues, and other factors over the course of several years.

This will be a four-part series, exploring in turn the following:

Creating an Institutional Vision

The Design Competition

The Importance of Programming

Designing for Impact

Creating an Institutional Vision

Historic photo of Robert Bruce’s home

The Bruce museum is located approximately 35 miles east of New York City. The history of the museum is one of humble origins. It began life as a home, originally owned by Robert Bruce.

In 1908, he deeded his property to the Town of Greenwich, stipulating that it be used as “a natural history, historical, and art museum for the use and benefit of the public.” The first exhibition ever at the Bruce Museum took place in 1912 and featured works by local artists known as the Greenwich Society of Artists.

It took until 1918 until the first museum director was installed. As the museum was technically the town’s property and under the town’s operation the town oversaw hiring staff, including the Director who, in the beginning, was unpaid.

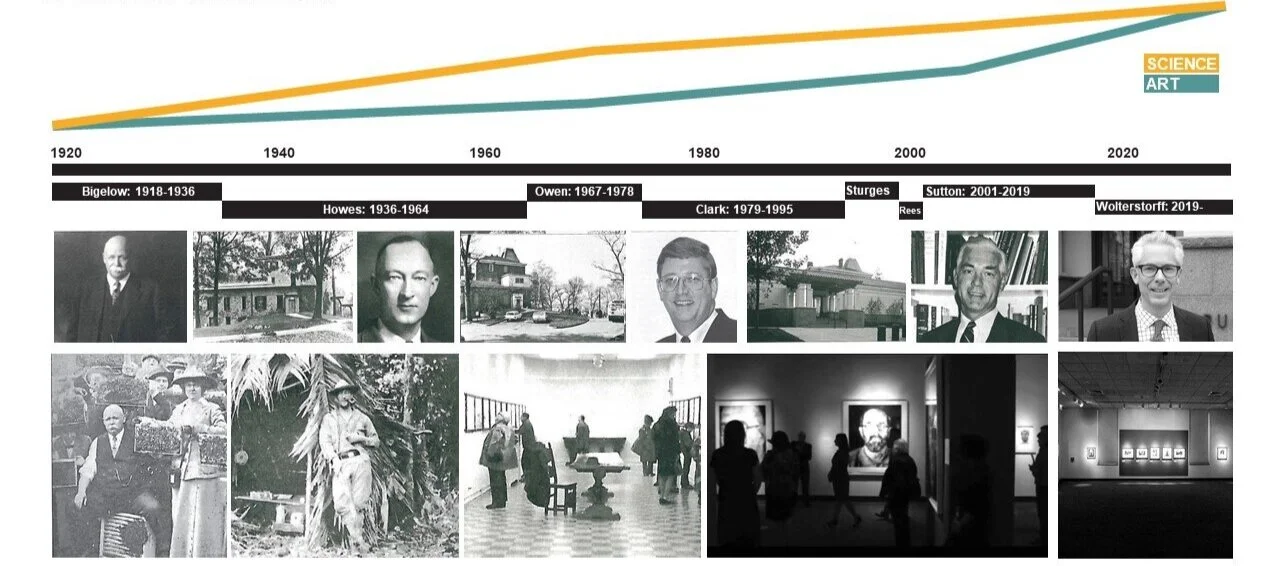

A brief timeline of Bruce Museum Directors over the years.

In the 1940s, the museum’s second Director held ambitious plans to expand the building, intending to abandon the original structure on the northern parcel and build a separate structure connected by walkways along the hill. It was never built.

In the 1950s, the interstate was built south of the railroad line. The sum of the land was in eminent domain, which allowed for some compensation to the museum and a small addition was built tethered to the original structure. But nonetheless it was a still a house, with small rooms, and the addition did little to disguise that fact..

The entrance to the Bruce following the 1992 renovation.

In 1992, the Bruce Museum undertook a complete renovation of its 139-year-old building. It got built on time and on budget, but several shortcuts were made, and the resulting project was not one that could sustain the museum into the future. Nonetheless, the small success of this building was such that the Bruce knew they would eventually have to expand further.

In the mid-2000s they began discussions with architects on opportunities for expansion of the museum.

Eventually, after 2008, after several engagements with architects that fell short, the Bruce decided to reevaluate their approach to hiring an architect. They had found themselves in a difficult position. A sort of endless slog of trying to get to a better building and having circumstances and disagreement get in the way. The museum turned to the AIA to see whether they could assist in hiring an architect. While the AIA had no clear prescriptions, they were able to point the Bruce in the direction of Reed Kroloff and his firm jones|kroloff.

Reed’s firm occupies an interesting position. In a way, they are matchmakers, adept at pairing client to architect--an entity who can make the language sound the same to both parties.

His firm often finds similar issues across vastly divergent projects. As a client, how does one begin to talk to an architect about what it is you need to do, what it is you want to do, and how many architects are out there that might be good for your institution? And where does one find them, and is it okay if they’re not local?

In short, “what are the things I need to know as a client that will enable me to work successfully with an architect?”

There are several things that are fairly consistent in the equation Reed’s firm offers. One near constant, is that exploring ways to hire an architects is something clients would be well served to approach early in the process -- almost the minute you decide you’re going to move forward with a project – even if you are someone who knows a lot about architecture.

As a first step, following initial discussion about vision and mission, Reed’s team began compiling a list of architects that had done the kind of work that might make them appropriate for the Bruce. Although there were no prerequisites for inclusion (one not even need to have completed a museum project), EskewDumezRipple was fortunate enough to be included in this initial list, thanks in large part to several of our national museum projects, including the Louisiana State Museum and the Paul and Lulu Hilliard University Art Museum at ULL.

Once the team determined a list of architects that made sense, they were able to begin a winnowing process that moved the client towards a smaller selection of architects and closer and closer to an answer.

The architect selection process for the Bruce outlined by jones|kroloff.

Reed encouraged the Bruce to conduct their own personal “sniff test,” one he readily advocates for his clients: “When selecting an architect, you have to imagine that you’re going on a very, very long ride in a very, very small vehicle. Who do you want to be with?”

Stay tuned for Part II, “The Design Competition,” coming soon.