Redesigning the Bruce for a Modern Audience | Part II - The Design Competition

This is Part II of a four-part series recapping a recent presentation given at Building Museums 2020 that explores the nearly ten years of collaboration renovating and expanding the Bruce Museum.

EDR’s original submission cover for the Bruce Museum Competition

The Design Competition

Shortlisted, and then ultimately requested to participate in the design competition, EDR found itself in a situation we visit somewhat infrequently. As architects, we don’t always do competitions. Most of our projects come via the typical RFP/interview/”try to find a fit” process without necessarily doing a design concept. But there have, on occasion, been a number that we’ll pursue this way.

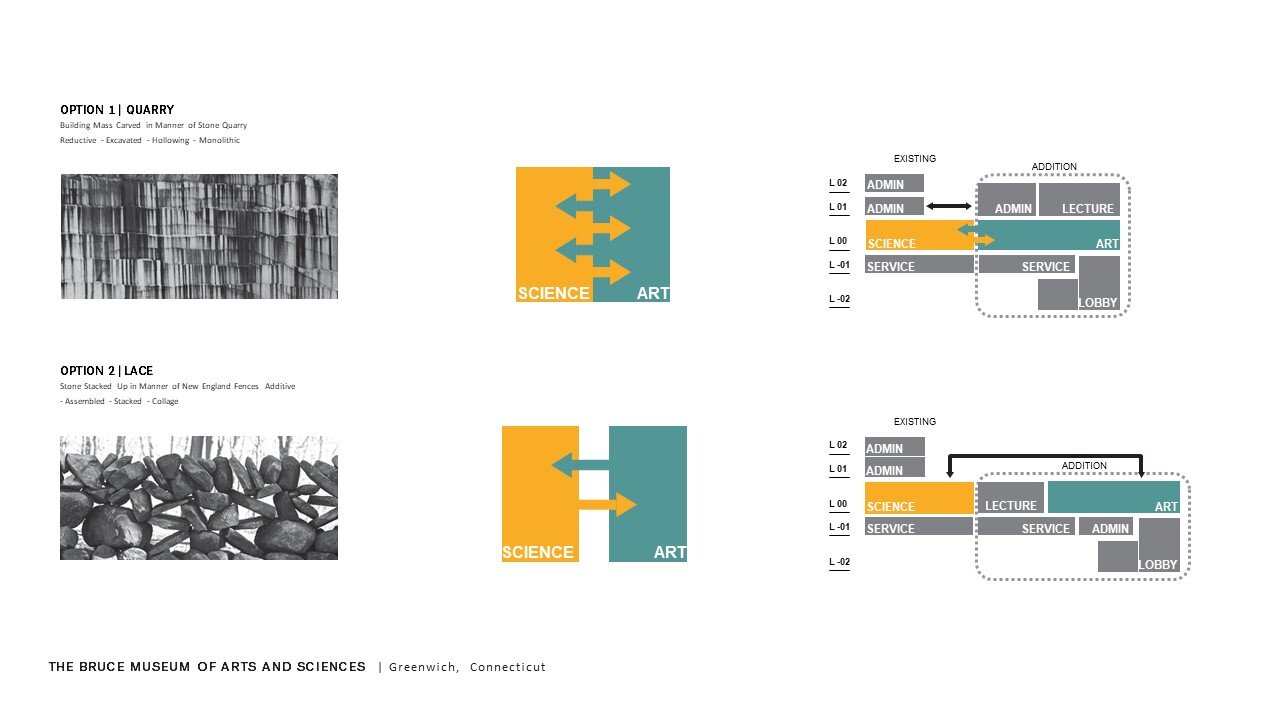

The important thing for us, is that we are trying to find the right fit, for both ourselves and the client. When we typically work, the answer has to build out of a dialogue. The problem with competitions we find, is they preclude that conversation. However, it is an interesting way to see how someone might work in the context of a given problem. What we found unique about this competition, unlike some others, was that we were asked to do not a single scheme, but multiple schemes, two in particular. The way this was framed to us is that the Bruce was more interested in seeing how we thought, not necessarily what a building proposal might be. Anyone who has ever gone through a design competition will quickly realize that it’s exceedingly rare that a winning competition entry gets built in much the same way it’s originally presented.

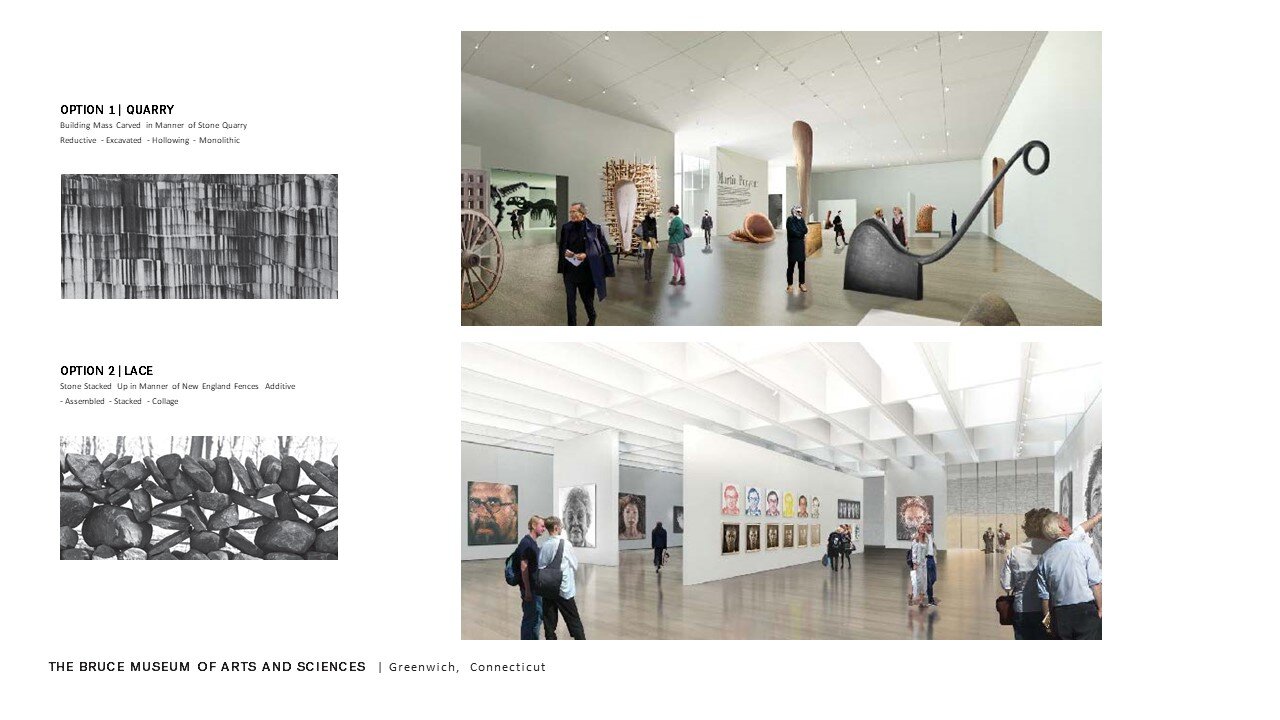

With the Bruce, though, we saw opportunities to build a project that could connect to its context, connect to its program, and connect to its community. All of those things were important to us as architects. We had never done an “art and science” museum. We had done museums with interpretive exhibit components, history museums, science museums, and art museums, but we had never done one in which these were combined. As we did the research on the Bruce, this idea of the relationship between art and science, and the way in which they emerge as a curatorial experience within the existing museum became a powerful spark.

In fact, the Bruce’s concept is fairly unique in the world of museums, and starkly distinct when compared to a place like the Smithsonian, where buildings exploring different topics exist under the umbrella of an institution, but remain separate entities.

A diagram showcasing the difference in layout and curatorial approach between the Smithsonian network of museums and the Bruce Museum on the right.

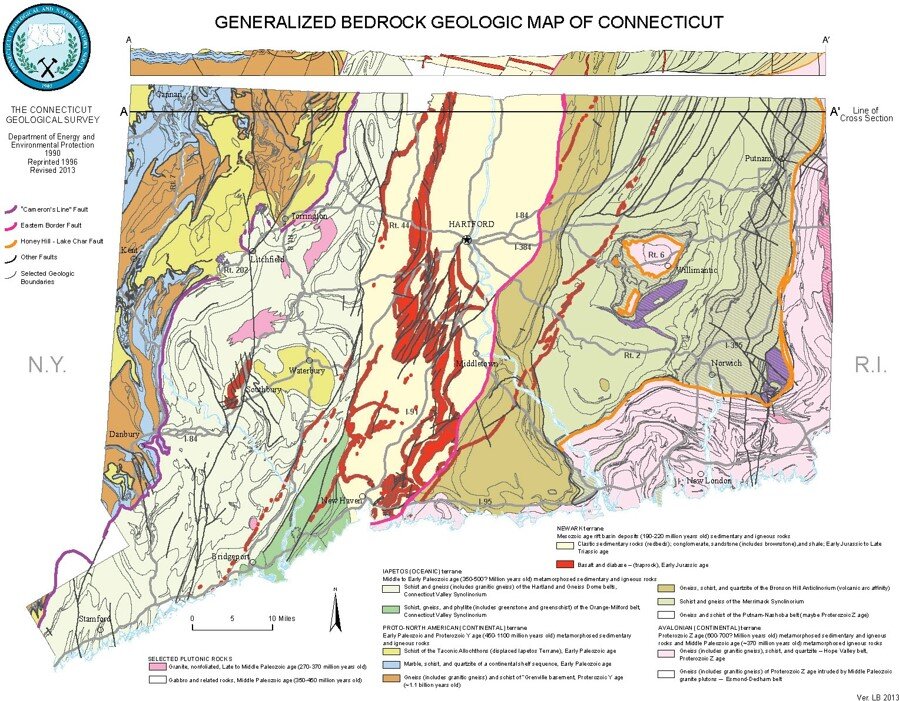

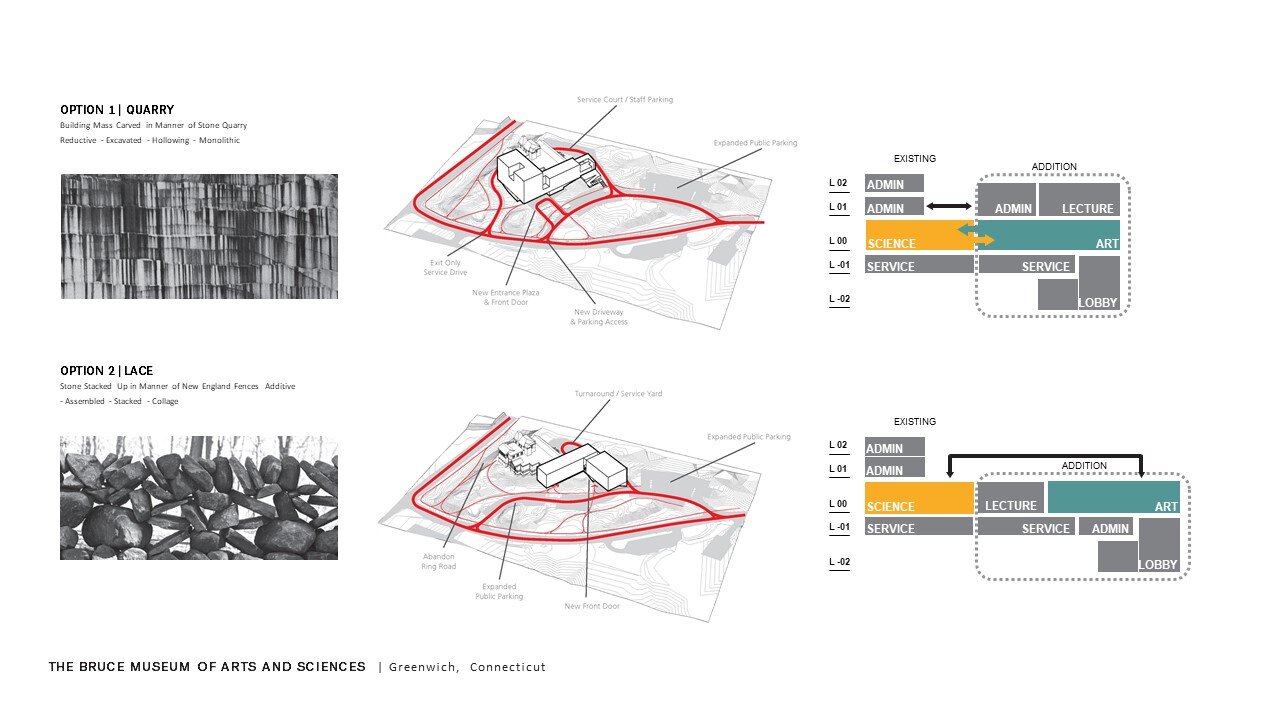

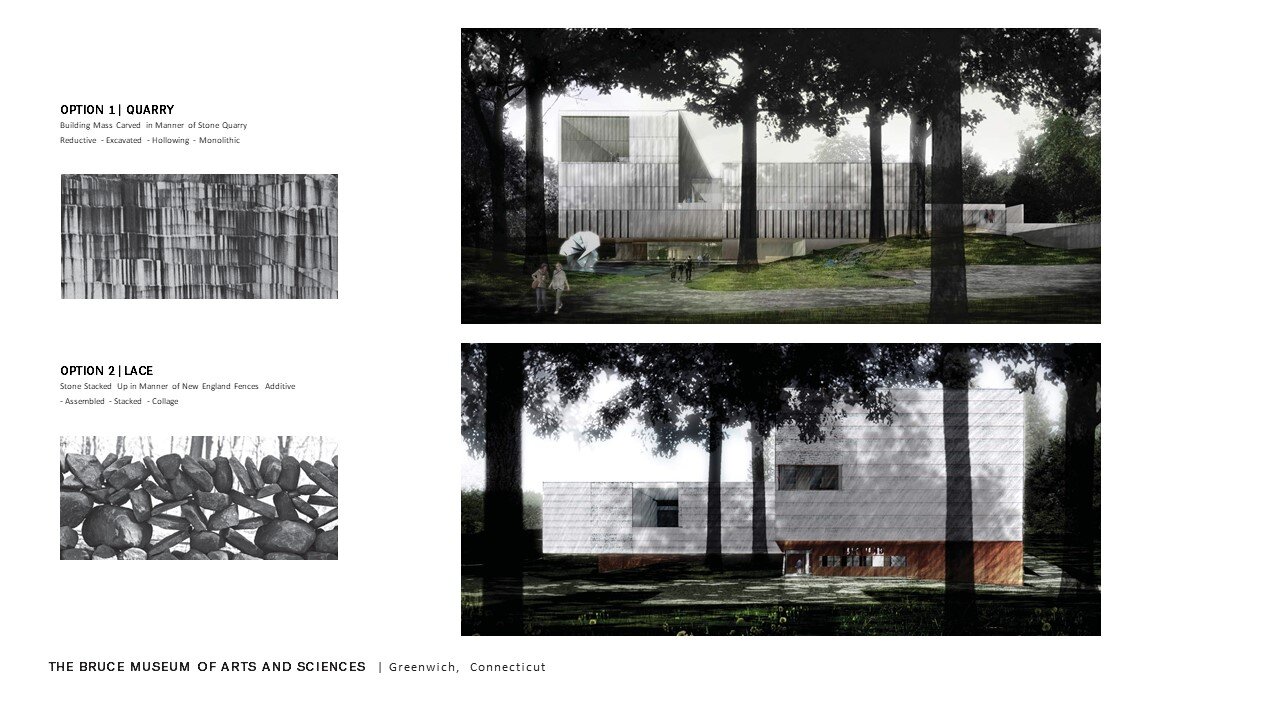

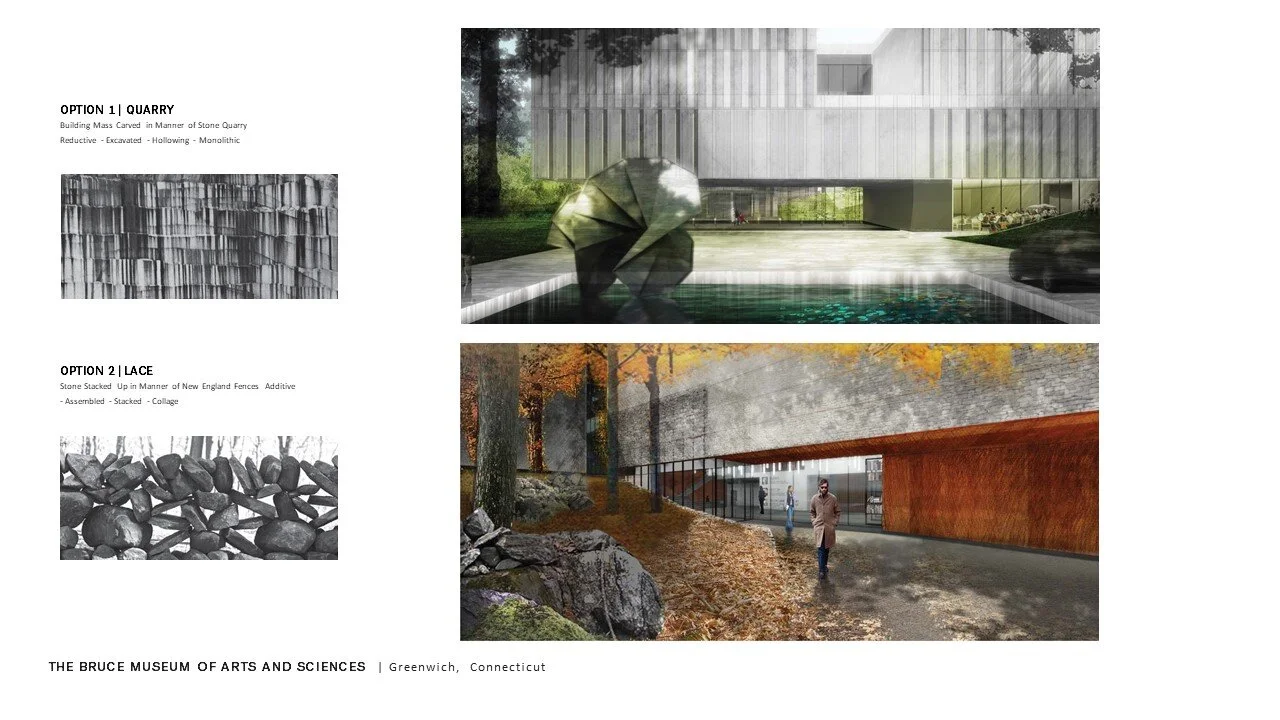

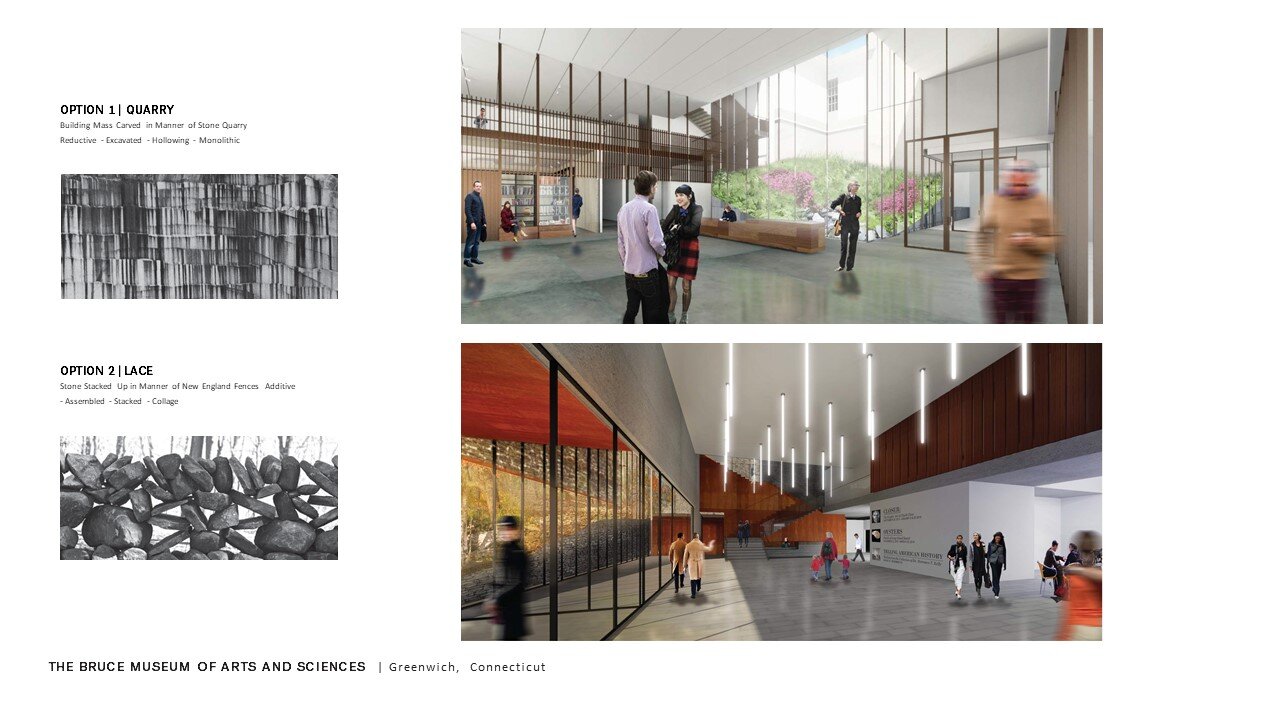

The other thing that was interesting, particularly for a firm from New Orleans where a six-inch incline over two miles long is a slope, was working in the context of New England and the Connecticut coastline. The original house was built on a hill in this bucolic park, and the idea of a museum embedded in the park, rather than laying on top of it, became the jumping off point for all of our concepts.

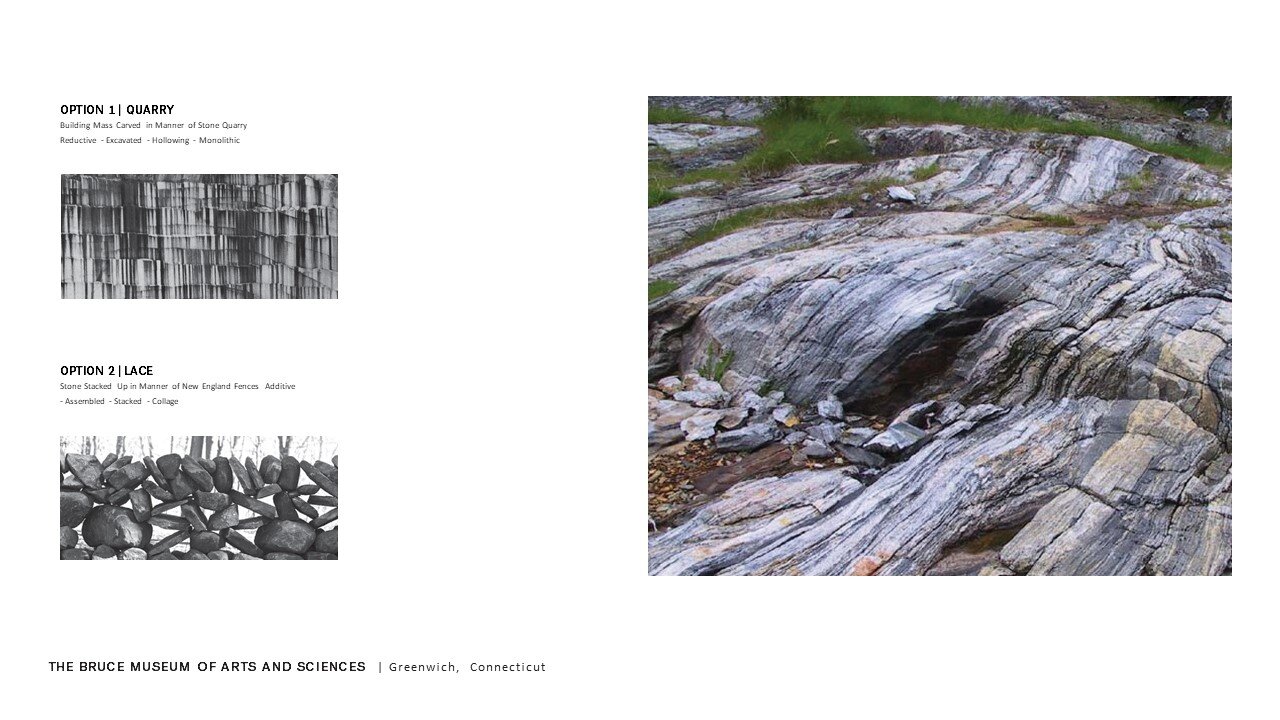

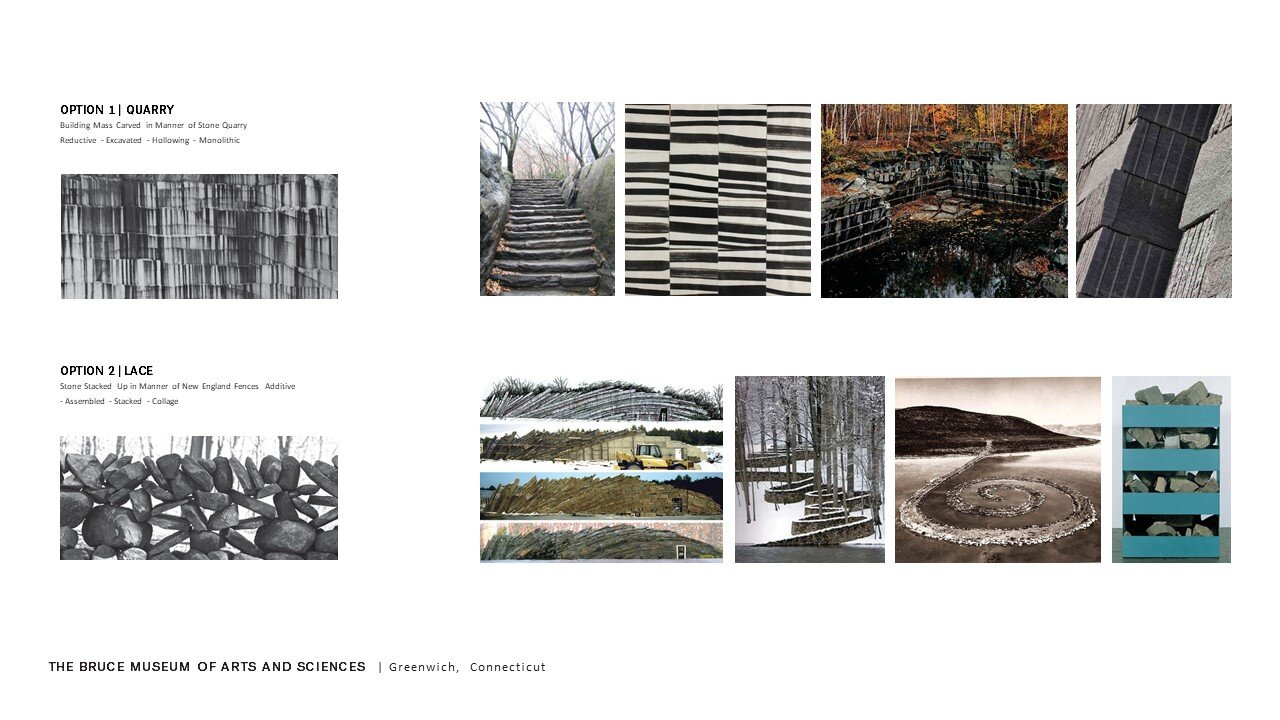

The surrounding landscape was also one composed, in many places, of jagged outcroppings of exposed stone. Throughout the region, one will find stone walls there that have been built by farmers, in which the stones are stacked. The result is a porous one, walls built up out of as much air as rock. The competition brief suggested two schemes, and so we developed two different schemes and two different attitudes that integrated stone that you might find along the Connecticut coast and quarries along the coastline.

As architects, we typically work in very close dialogue with our client about their problem, and often come up with many options of solving it. In this case we couldn’t do that. It was a competition, and with our two schemes we did our best to have that dialogue internally between the two ideas. We asked a lot of questions of ourselves and potentially the program, by coming up with two ways to solve it. Those two schemes evolved into two different attitudes about how the building would be arranged on the site. Both schemes connected to the existing building. In our mind, operationally, it made a tremendous amount of sense to have those two connected.

Again, all of this was done with a design produced in the absence of a conversation with the client. We did, as part of our team, include a woman and a firm that we’ve worked with on all our museum projects, Marcie Goodwin of MGMP. Marcie is a museum planner and programmer, and because we had only the sketches of a program, thought it prudent to bounce ideas off her and run an analysis of the given program. The project brief outlined a certain amount of net program – gallery space, café, etc. – and made a reasonable conclusion about the resulting size of the building, essentially 30,000 SF net.

Our experience over the years indicated that this initial estimate would instead need to be much larger, as the gross areas were going to add a great deal more than anticipated. And so while the competition allowed us to show a set of ideas, it was clear that they were going to change as the program did.

Stay tuned for Part III, “The Importance of Programming,” coming soon.