Redesigning the Bruce for a Modern Audience | Part IV - Designing for Impact

This is Part IV of a four-part series recapping a recent presentation given at Building Museums 2020 that explores the nearly ten years of collaboration renovating and expanding the Bruce Museum.

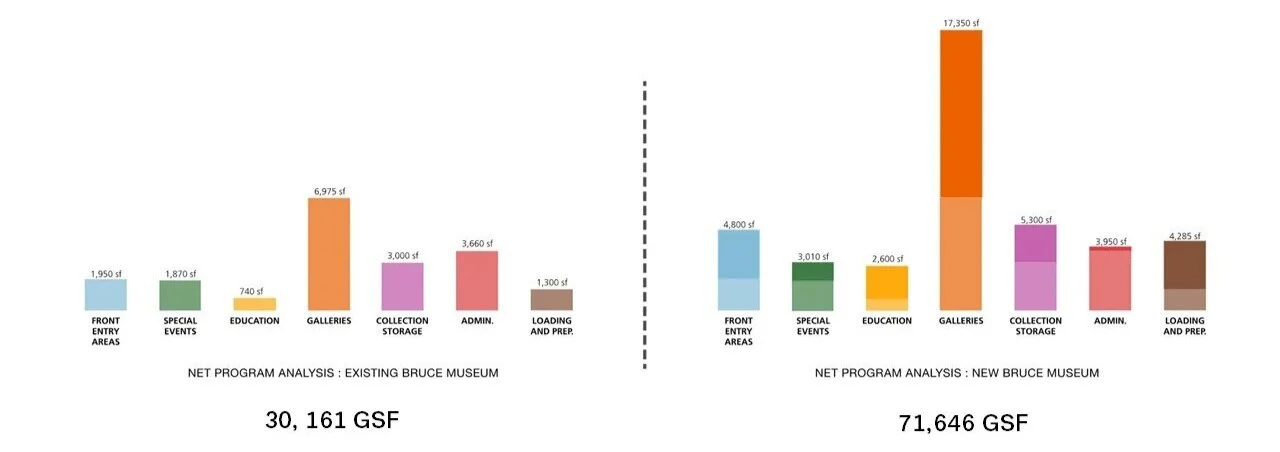

What our initial programming exercise with the Bruce showed was the importance of getting institutional buy-in on program, as it deeply impacts an institution and how it will support its vision. We ended up doubling the size of the museum, adding 40,000 SF of space, but we did not increase the square footage of every space from the original program proportionally.

A comparison of corresponding areas and square footage before and after Programming.

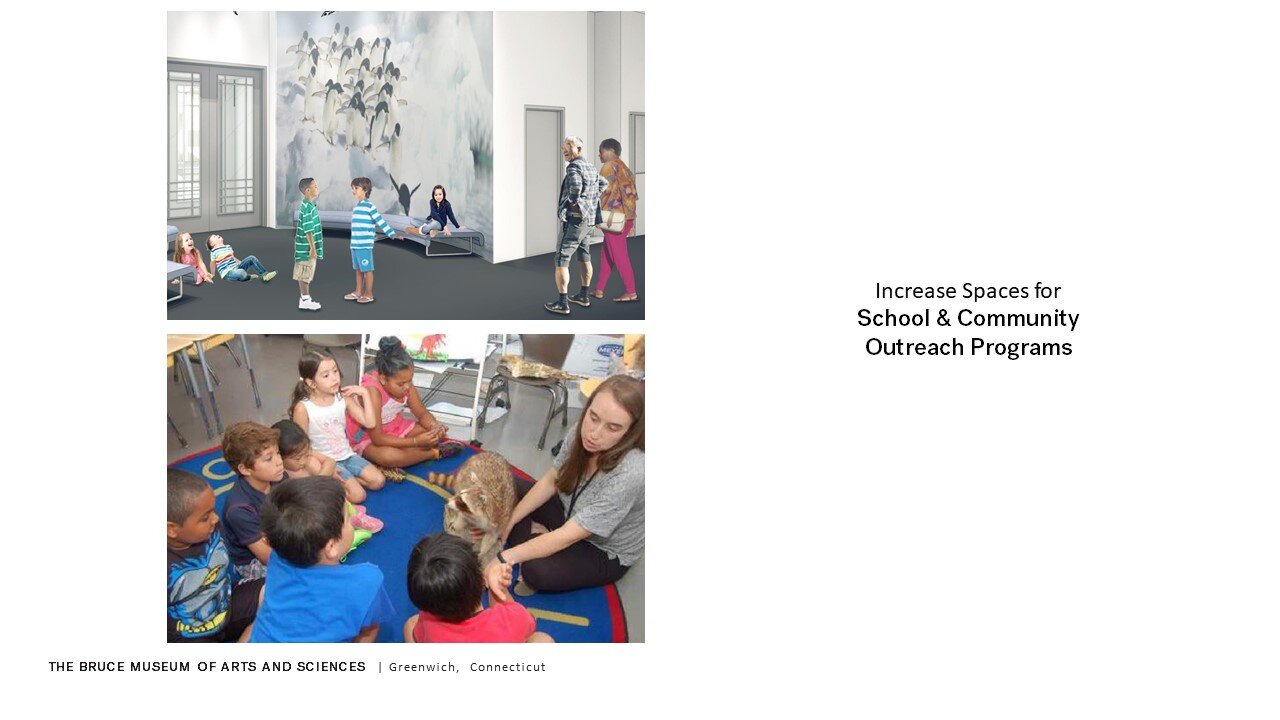

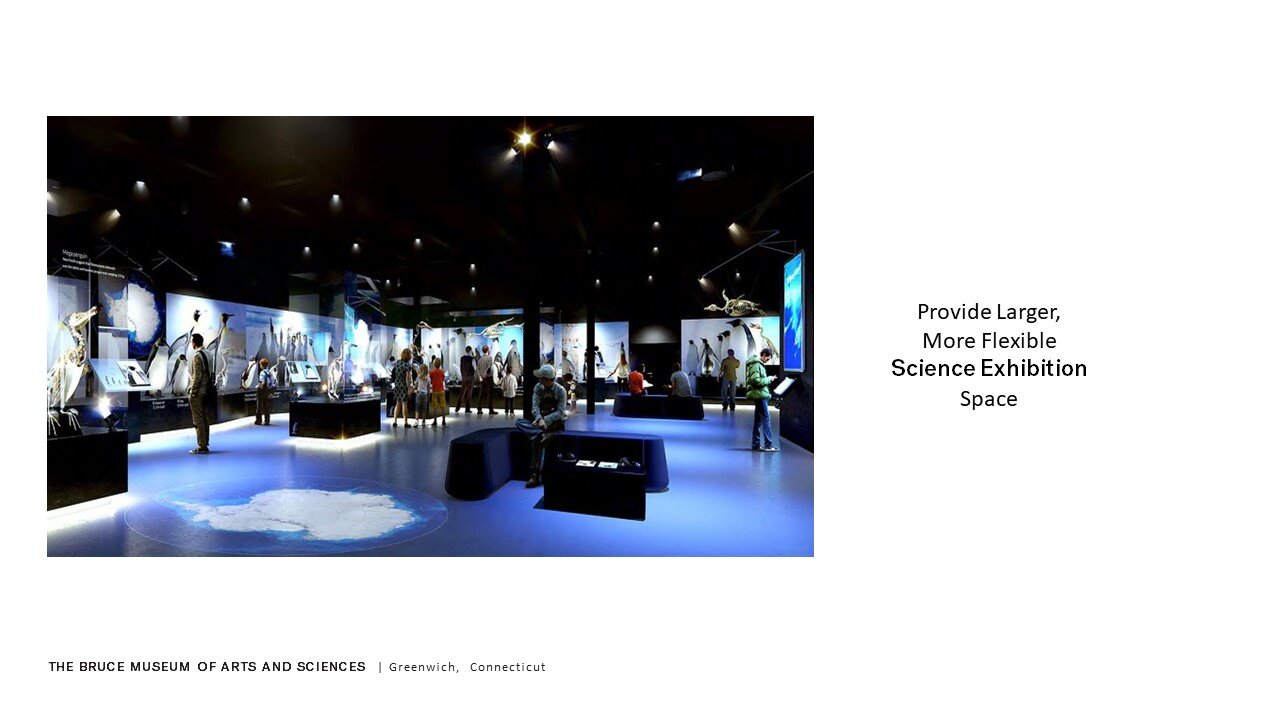

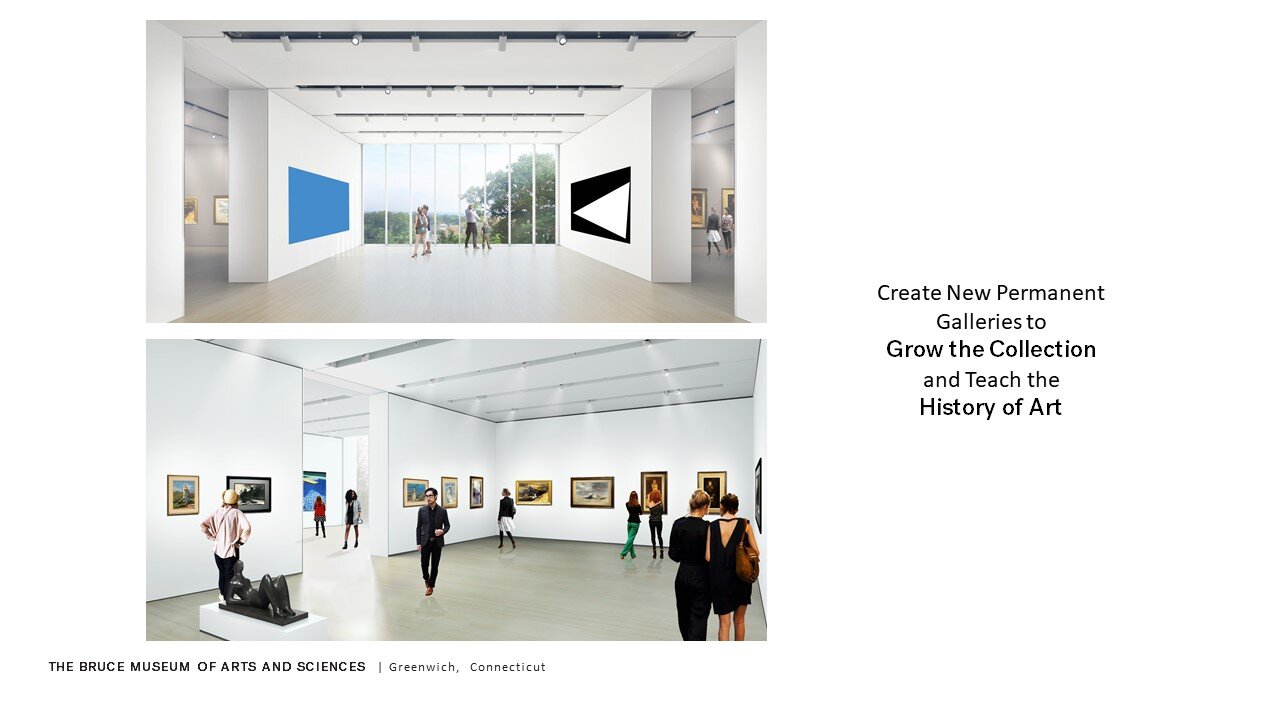

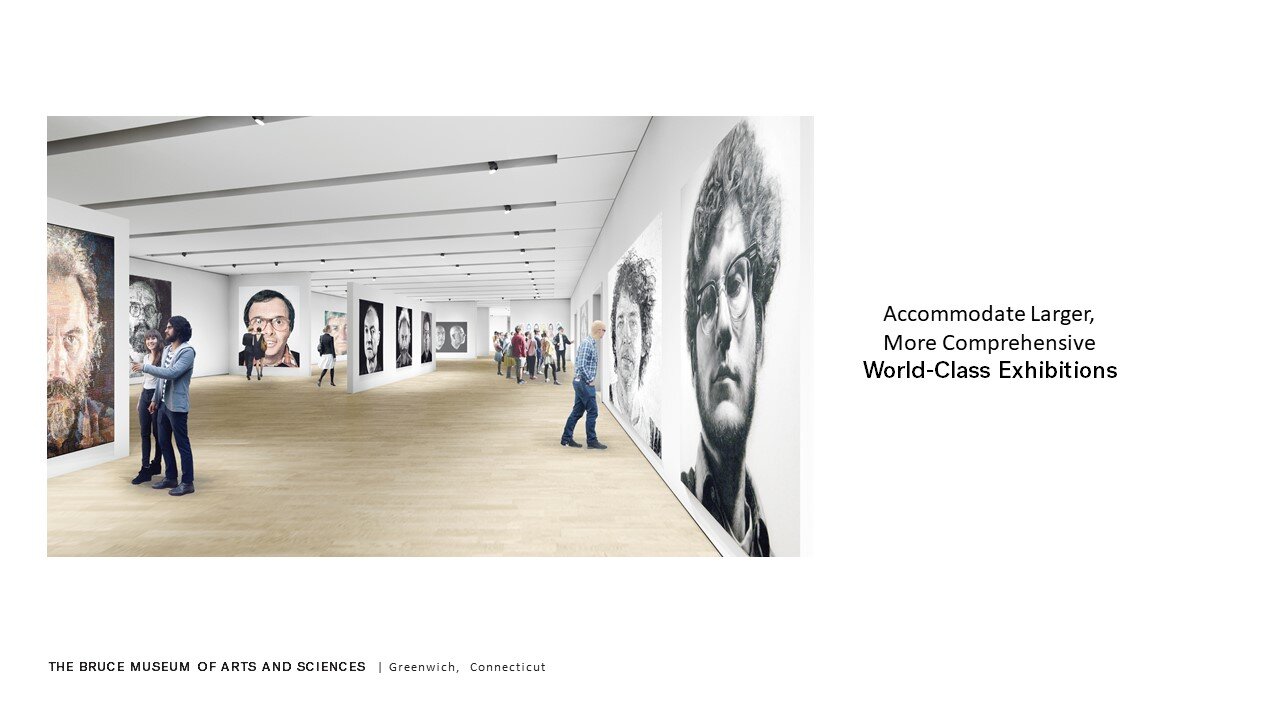

Education spaces, public spaces, and gallery spaces were all prioritized over spaces deemed less critical to the Bruce’s mission.

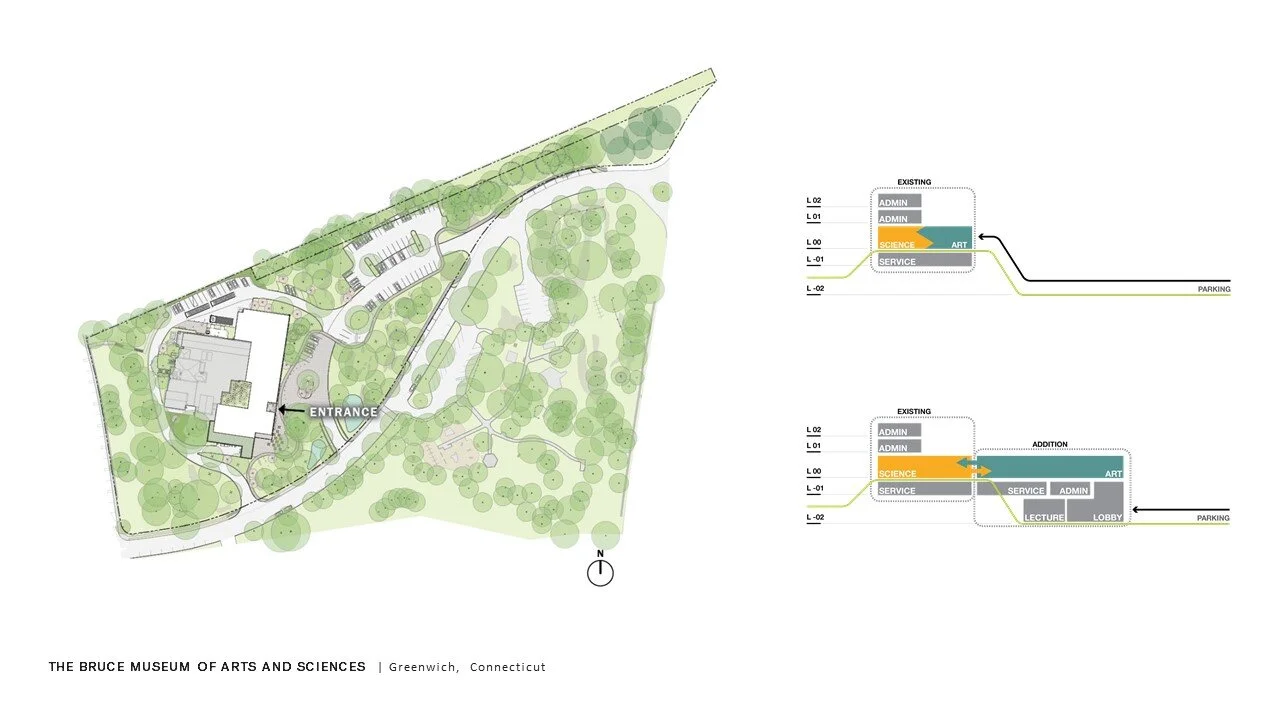

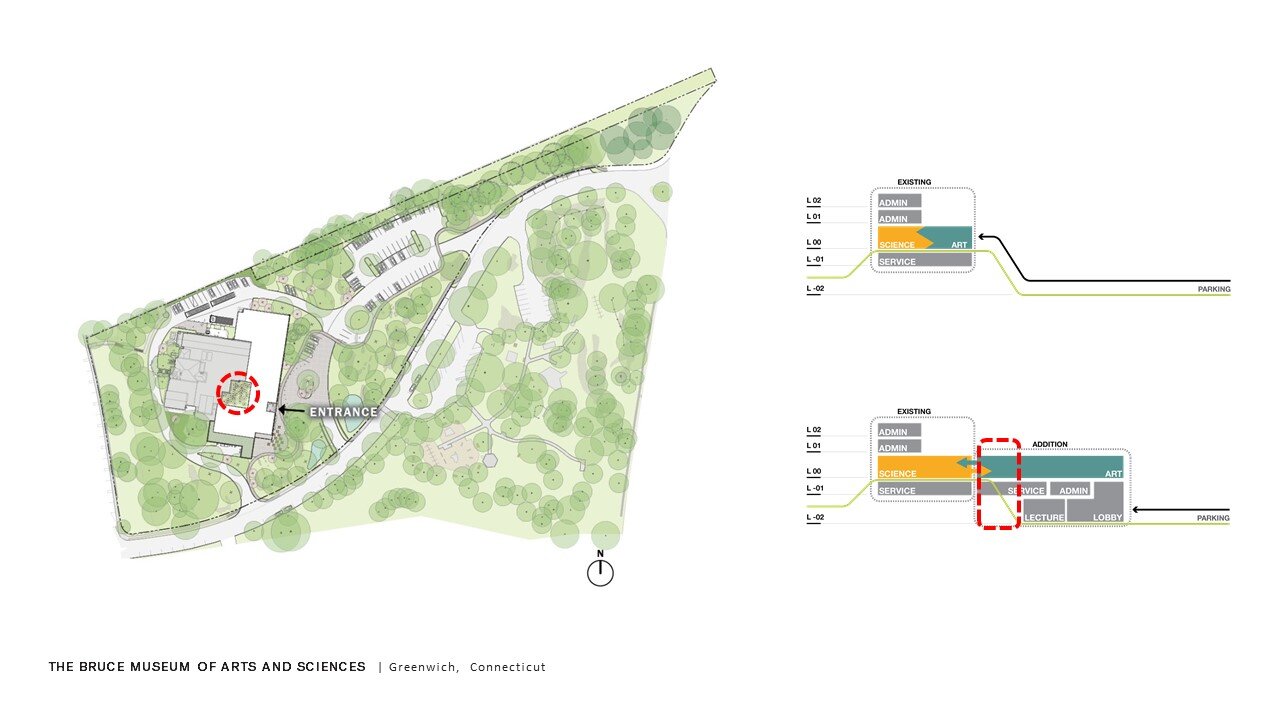

From a design standpoint, we had produced two schemes, and after engaging in direction conversations, the client expressed a fondness for aspects of both. They asked us develop a hybrid, especially now that the program had changed, to singularly address their needs. Returning to the museum on the hill, the building had always been historically accessed from the north side, which faced the interstate. The front entry, from the view of the adjoining parking lot, was almost hidden from view, and our design attempted to address the fact that you had to walk up the hill to find the front door.

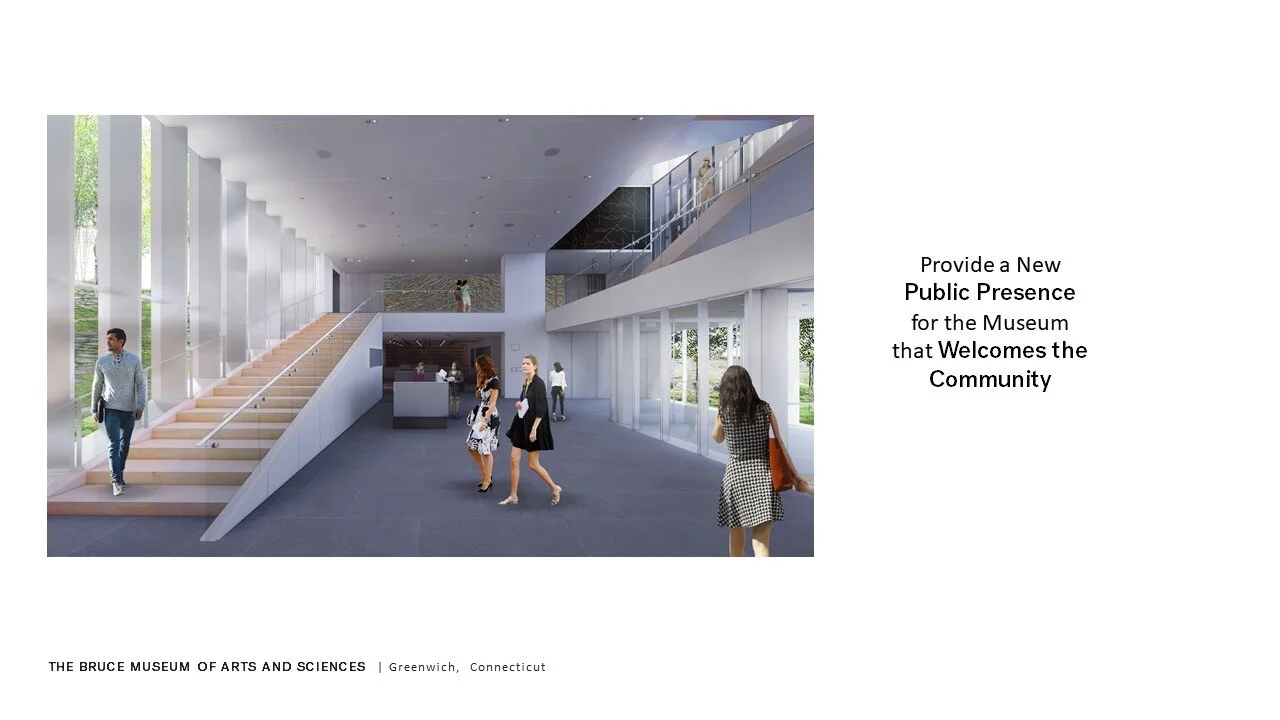

Because we were going to add 40,000 SF, the building was going to grow to the side and drop down the hill, which allowed us to create a new front entry at the elevation of the park, one truly connected to the park and the community. In this, we worked with Reed Hildebrand as landscape architects. As they looked at the site, they discovered a contour, the same elevation as our front door, that worked its way through the entire site. So the idea of connecting a visitor with an experience where one moves through the entirety of the site on a singular level was something that became very enticing. In addition to enabling us to express the site in an intense way, it also opened opportunities for art and wayfinding throughout the park.

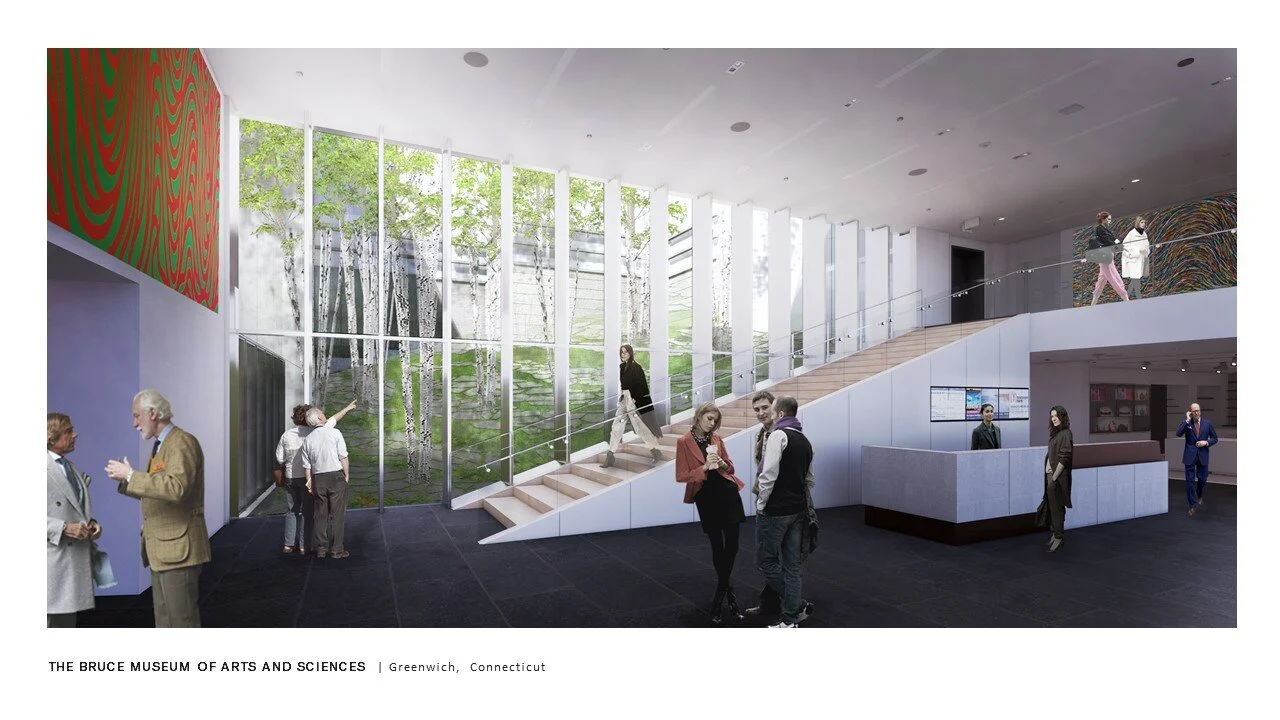

In terms of the museum’s design, because this was an addition that for the most part stood away from the existing house — Reed simultaneously worked with us to develop a courtyard space between the two structures that almost becomes an extension of the park into the museum.

The captured courtyard of the Bruce Museum designed in tandem with Reed Hildebrand.

A small “diorama,” this captured space reveals itself as you come into the lobby, with the far stairway following the slope of the hill up to the gallery level above.

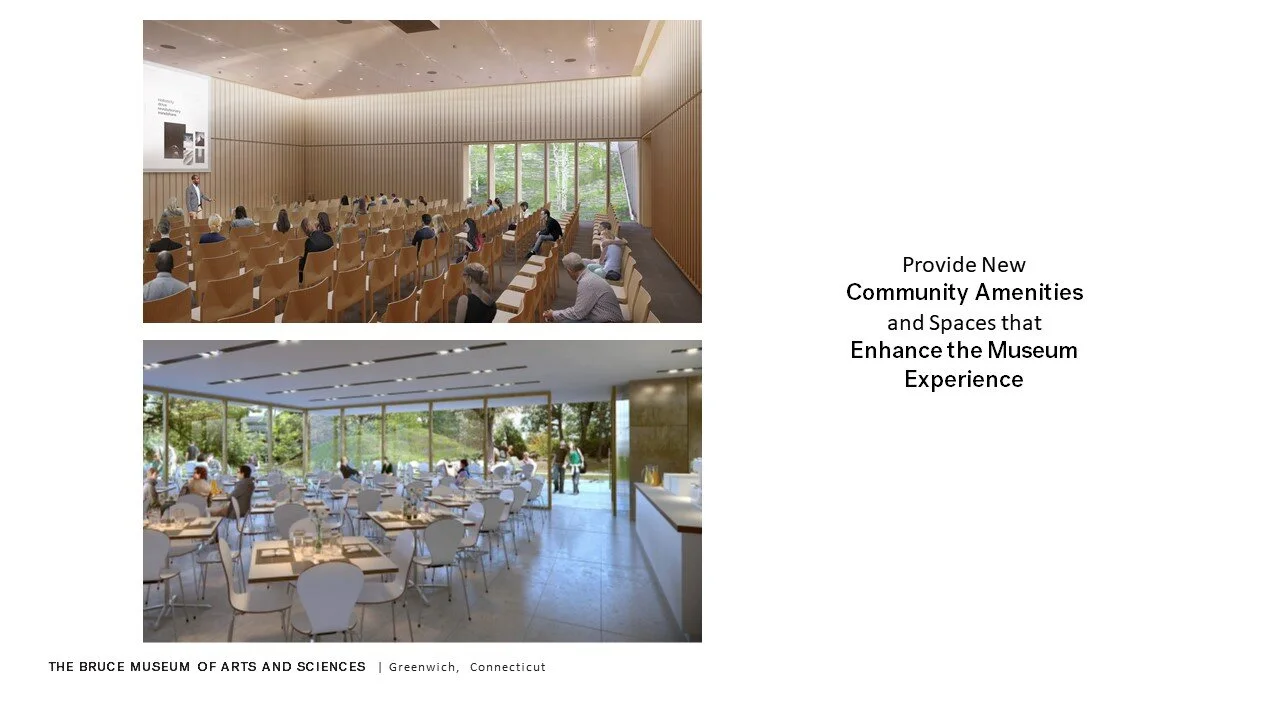

In terms of planning strategies, there were things we outlined in the competition and then carried forward because the museum specified them important. One museum, one front door. The notion of two galleries (science galleries in the existing structure, and art galleries in the new), but with both intimately connected, with opportunities to have curatorial shows that could cross-pollinate. The idea of a connection to the community via cafe, multi-use events space. Sustainability. Expanding the idea of a museum as not just a cultural destination, but an educational one.

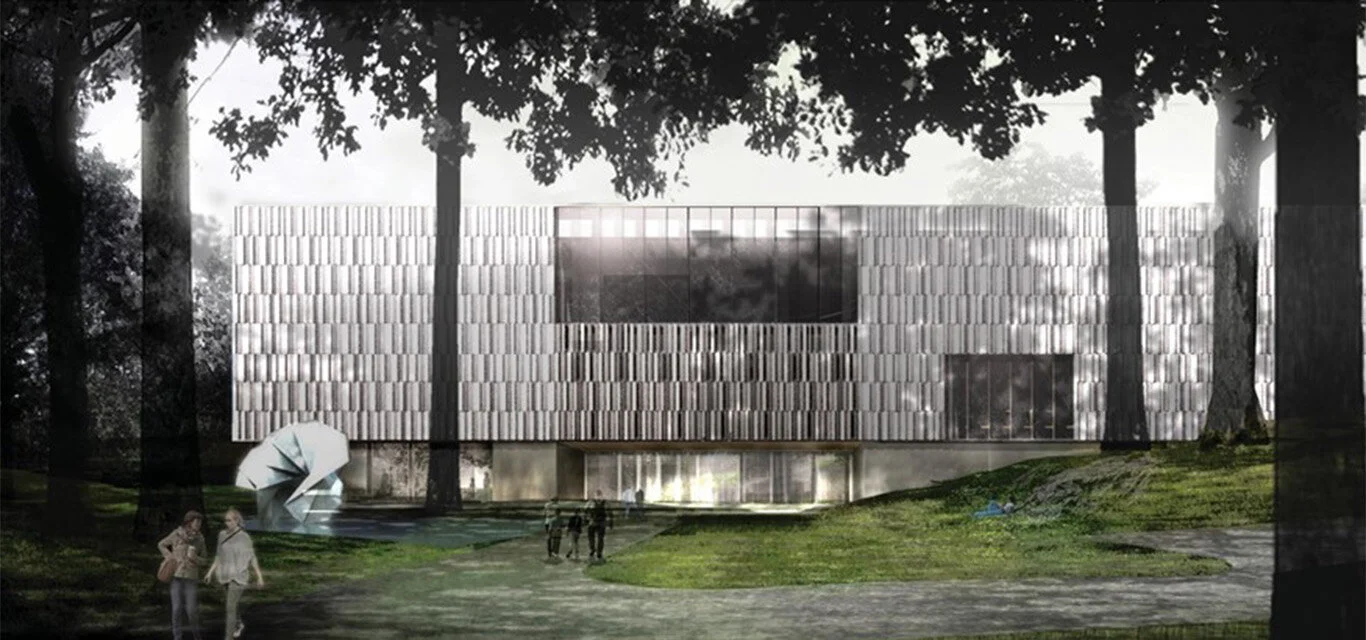

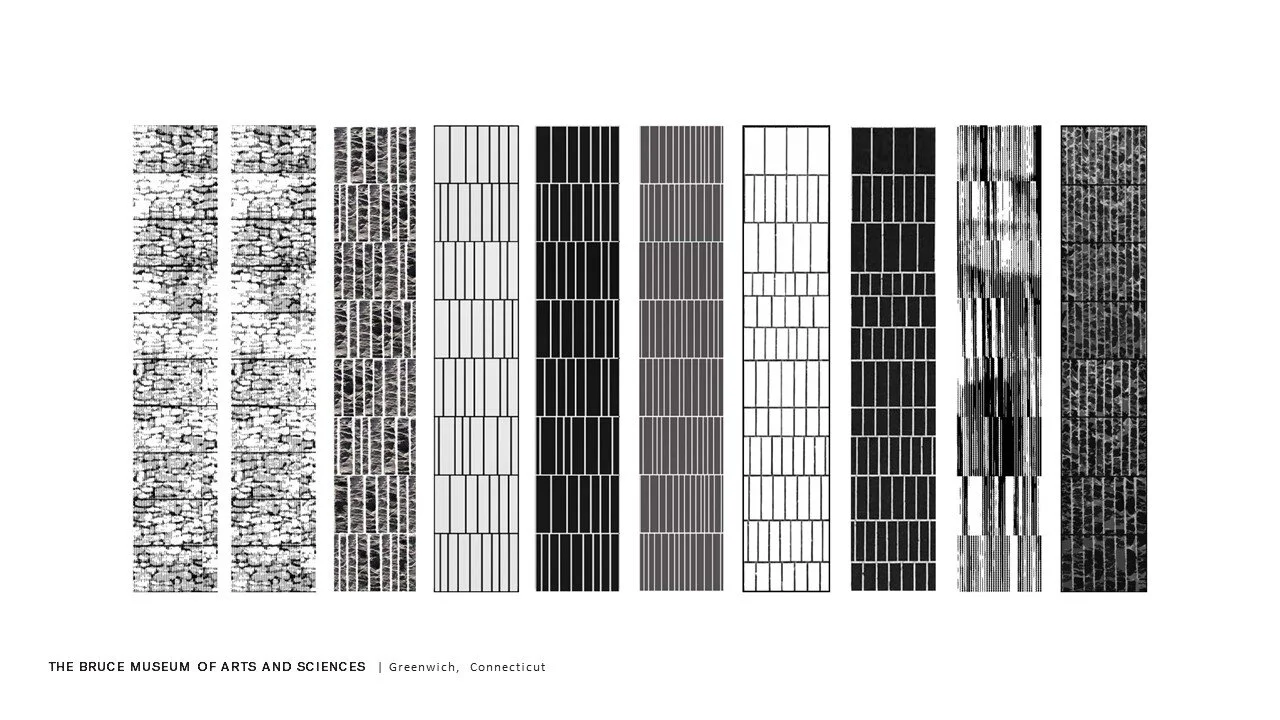

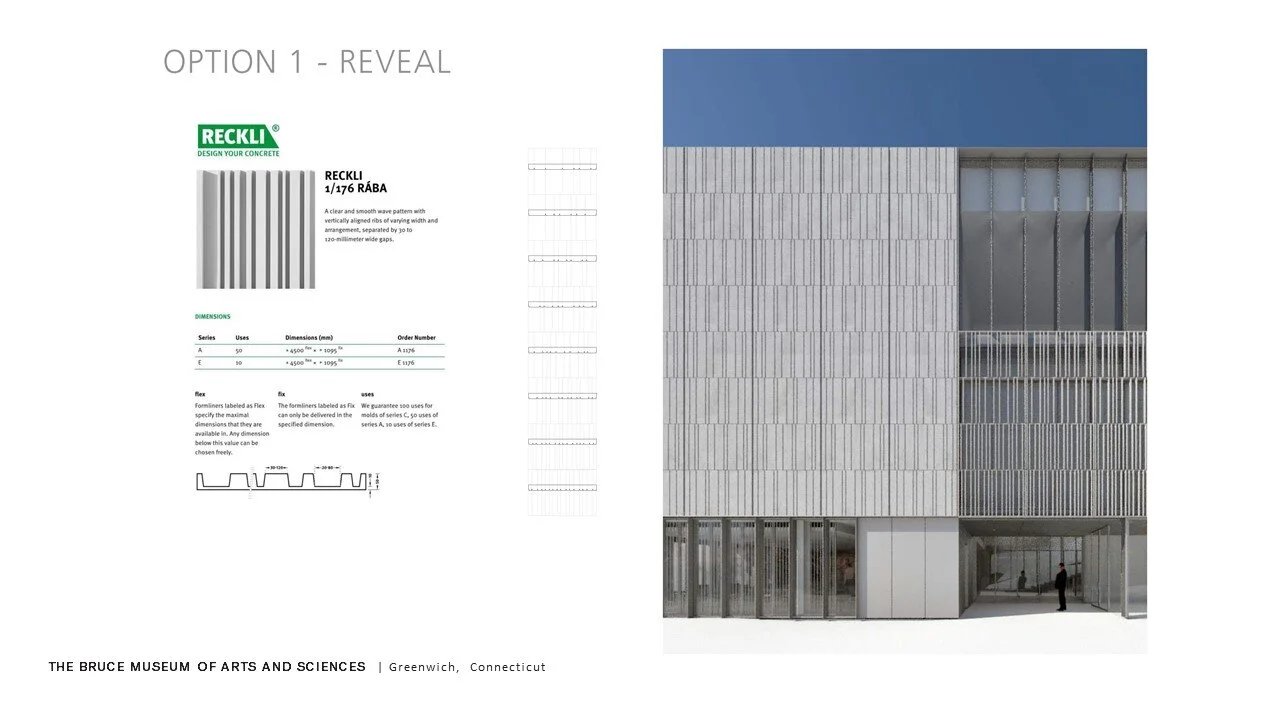

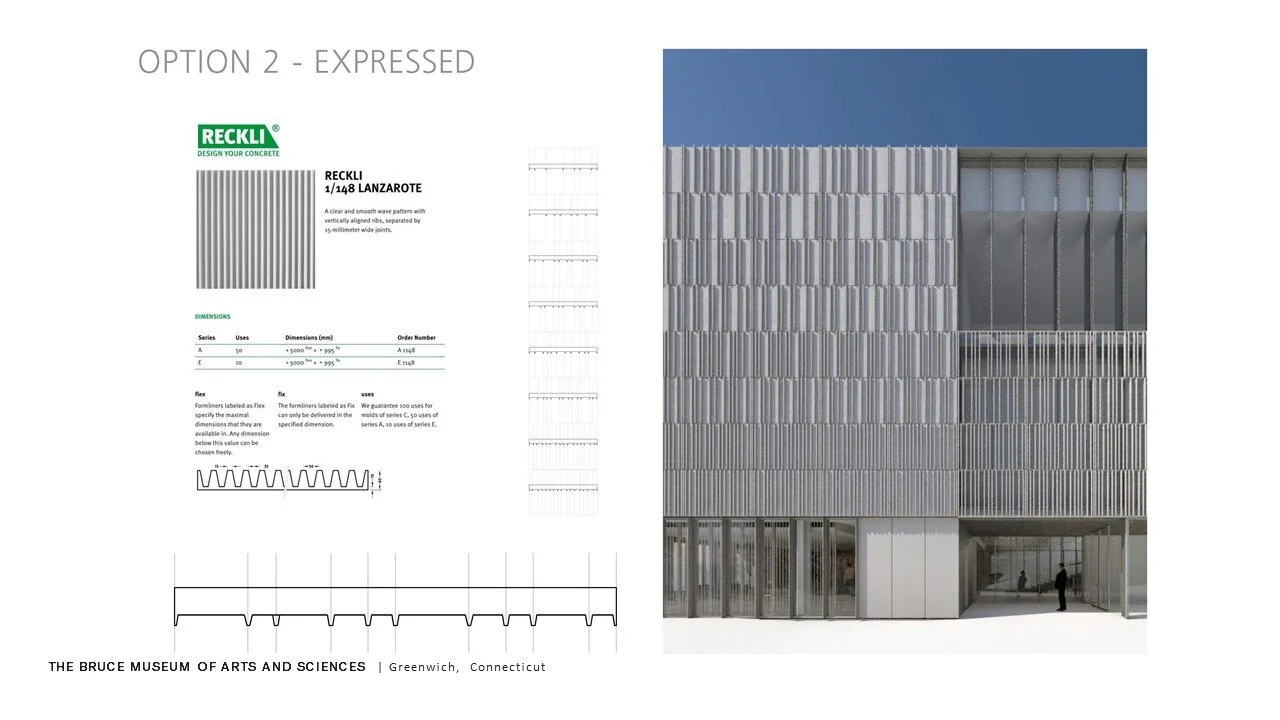

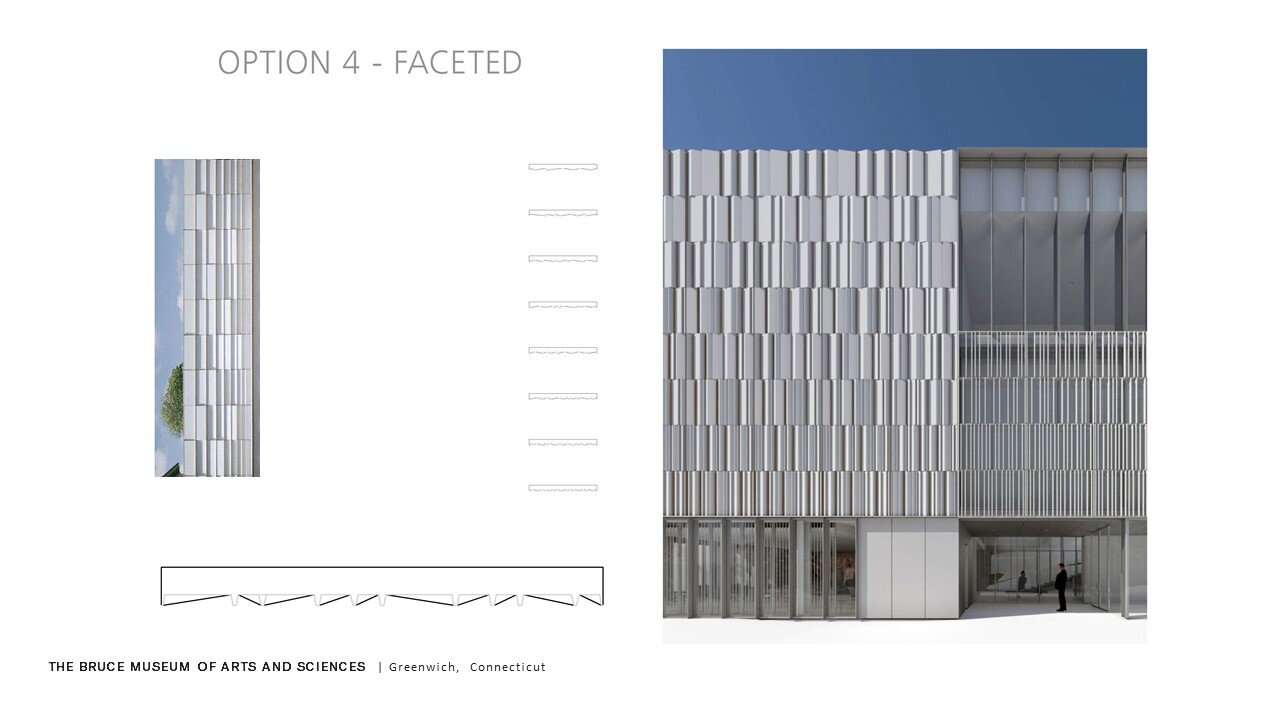

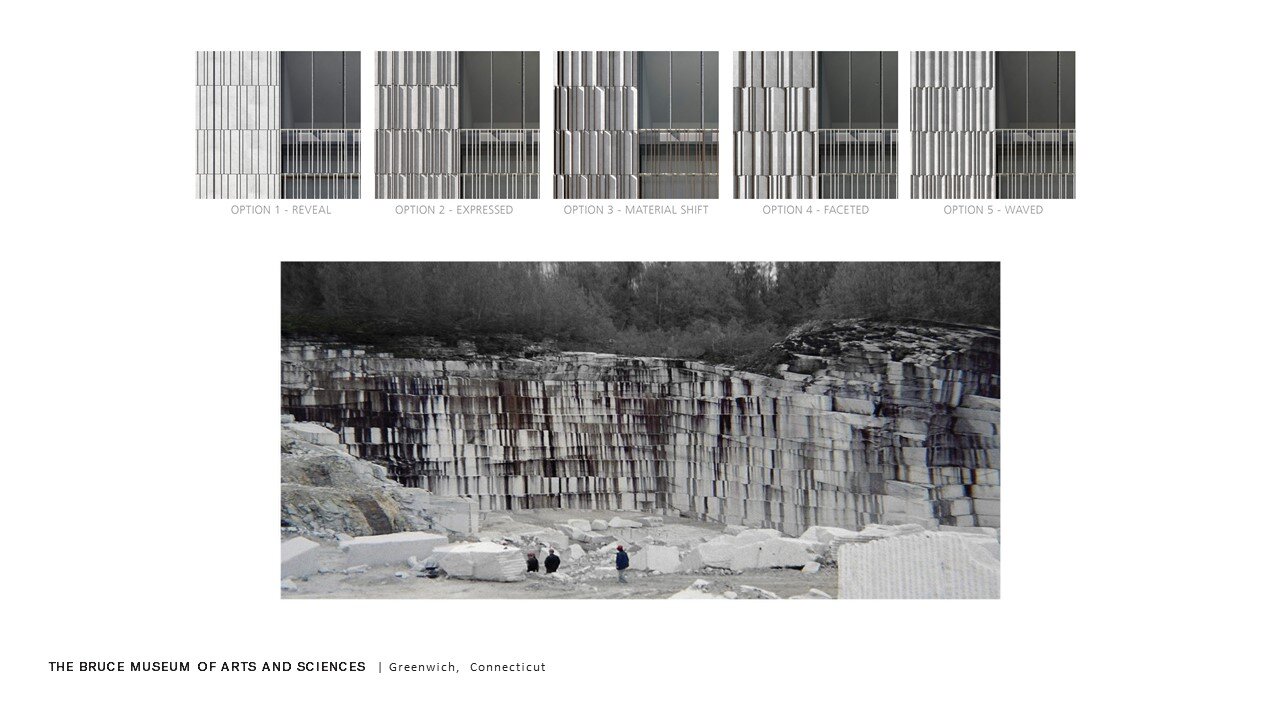

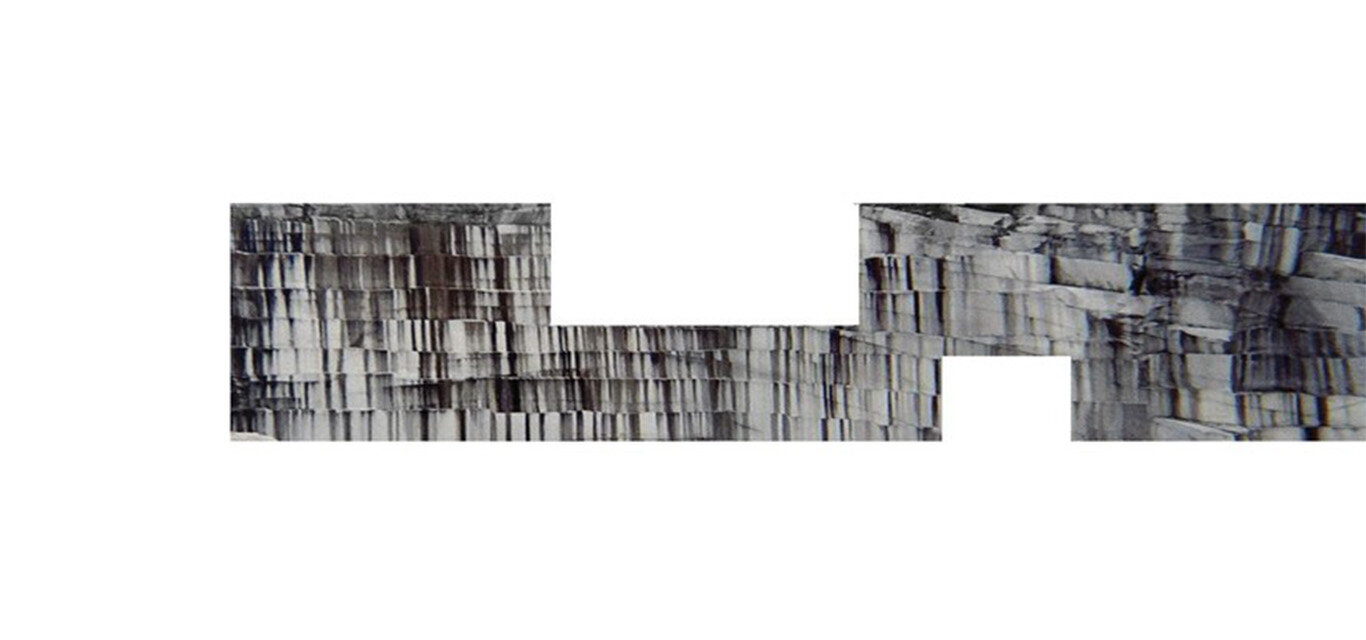

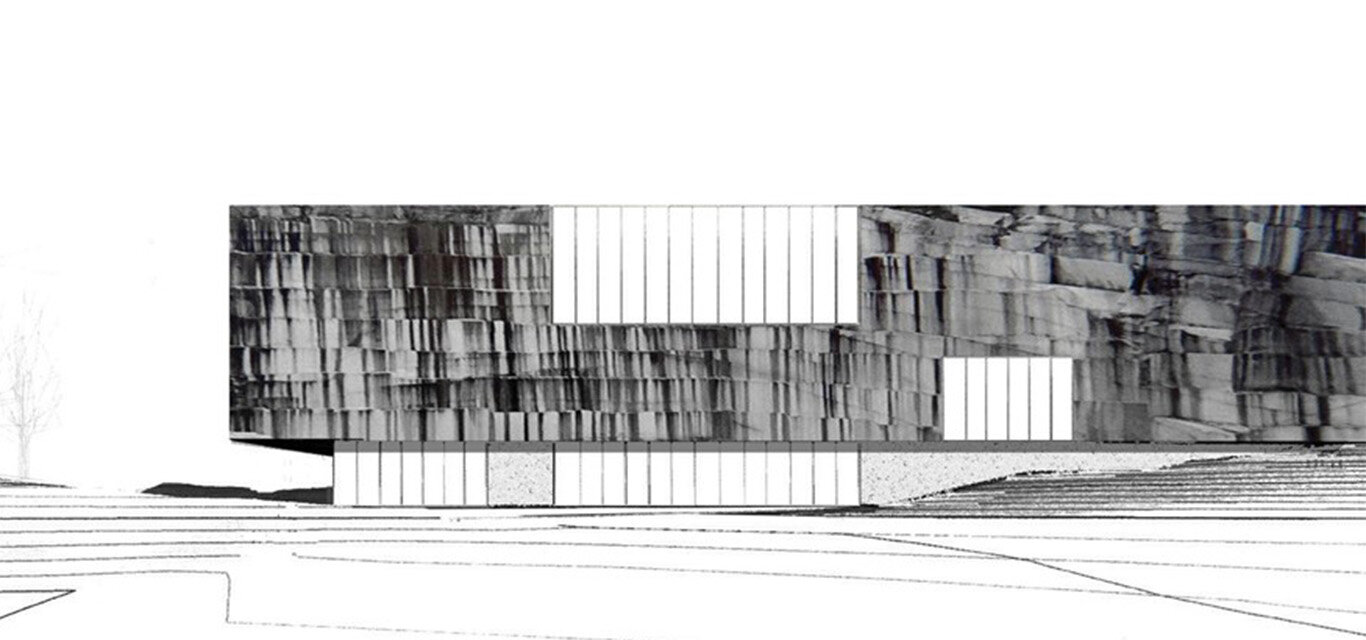

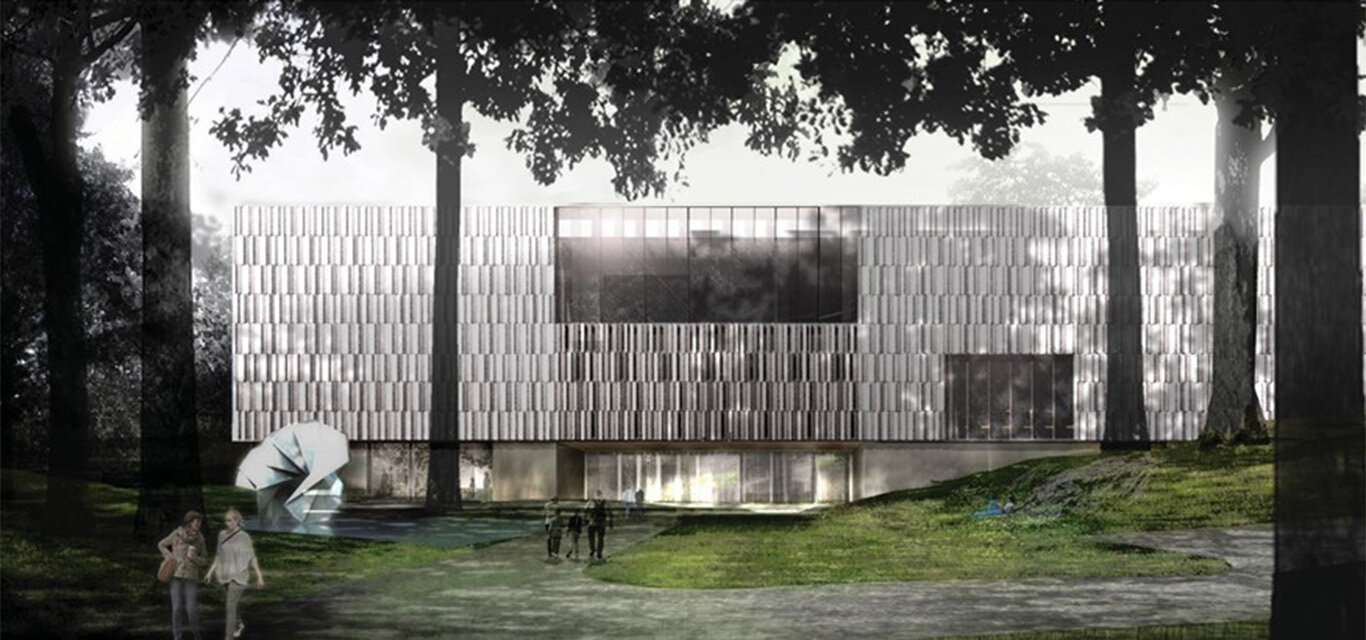

Naturally, no project is without its hurdles, and we realized early in the process, that a number of scope and budget alignments were required. What we did was work very closely with the museum to ensure that, first and foremost, the program needs of the institution would still be met. This is an issue that we deal with consistently as architects. How do you retain the fundamental concept that energized the entire project in the first place when faced with budget constraints? In this case we refrained from decreasing scope or square footage -- those were critical to the museum’s mission. What we did look at was transforming the skin of the building from a stone, to a cast stone. We did several studies to express this new result, and how it might still relate closely to our concept, one that maintained a contextual response to its surroundings, instilling opportunities to reflect the place and landscape in which it was built.

We returned to our notion of stone and the articulation of quarries and stone walls. We did extensive mockups and models in exploring this revised notion. In the end, we developed a faceted skin that will change appearance throughout the day with the light of the setting sun.

We’ll also soon be moving into a full-scale model on site, intended to generate further enthusiasm for the project.

We begin construction this summer.