Redesigning the Bruce for a Modern Audience | Part III - The Importance of Programming

This is Part III of a four-part series recapping a recent presentation given at Building Museums 2020 that explores the nearly ten years of collaboration renovating and expanding the Bruce Museum.

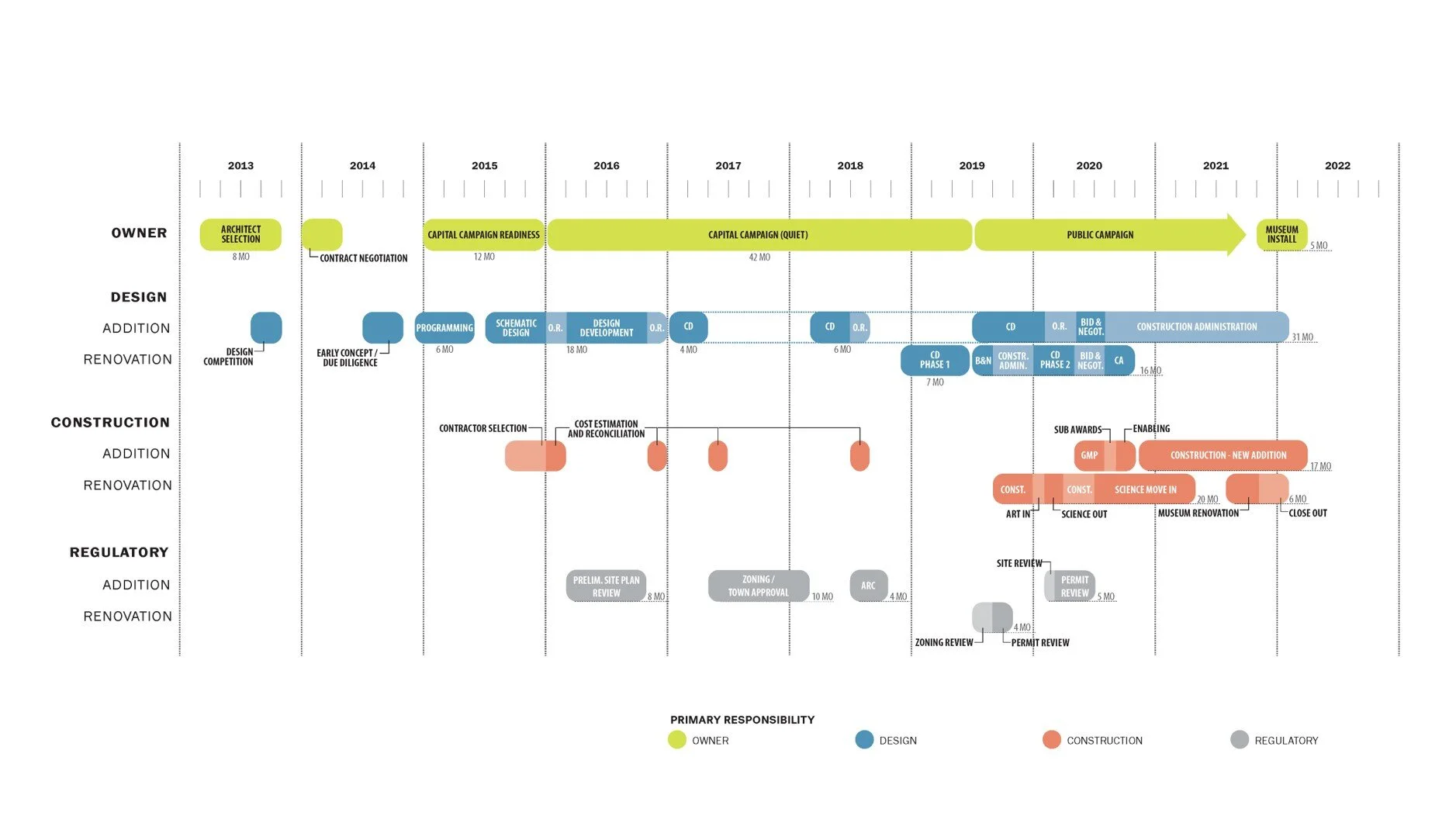

The schedule developed for the Bruce, which included line items for Programming, Capital Campaign Relations, and Public Campaign.

Ultimately, EDR was fortunate enough to be selected, and with our inclusion of a museum planner on our team, the museum quickly latched on to the idea of an extensive programming exercise prior to entering design. As architects, we took a backseat in this exercise and empowered Marcy Goodwin to work closely with the Bruce in revamping their initial program ideas.

The Bruce naturally had a rough idea of what they wanted and thought that was the program. They certainly wanted more community space. There was an existing lecture hall, but it was not big enough. There was no café, and they knew they wanted one to serve the public and make the museum experience richer. Similarly, they wanted to expand their store for revenue, and since they had collaborated with other museums on exhibitions, they realized their exhibition space was not big enough.

What they did not know was that wall space and holding space also count in the square footage, and that those costs are largely the same.

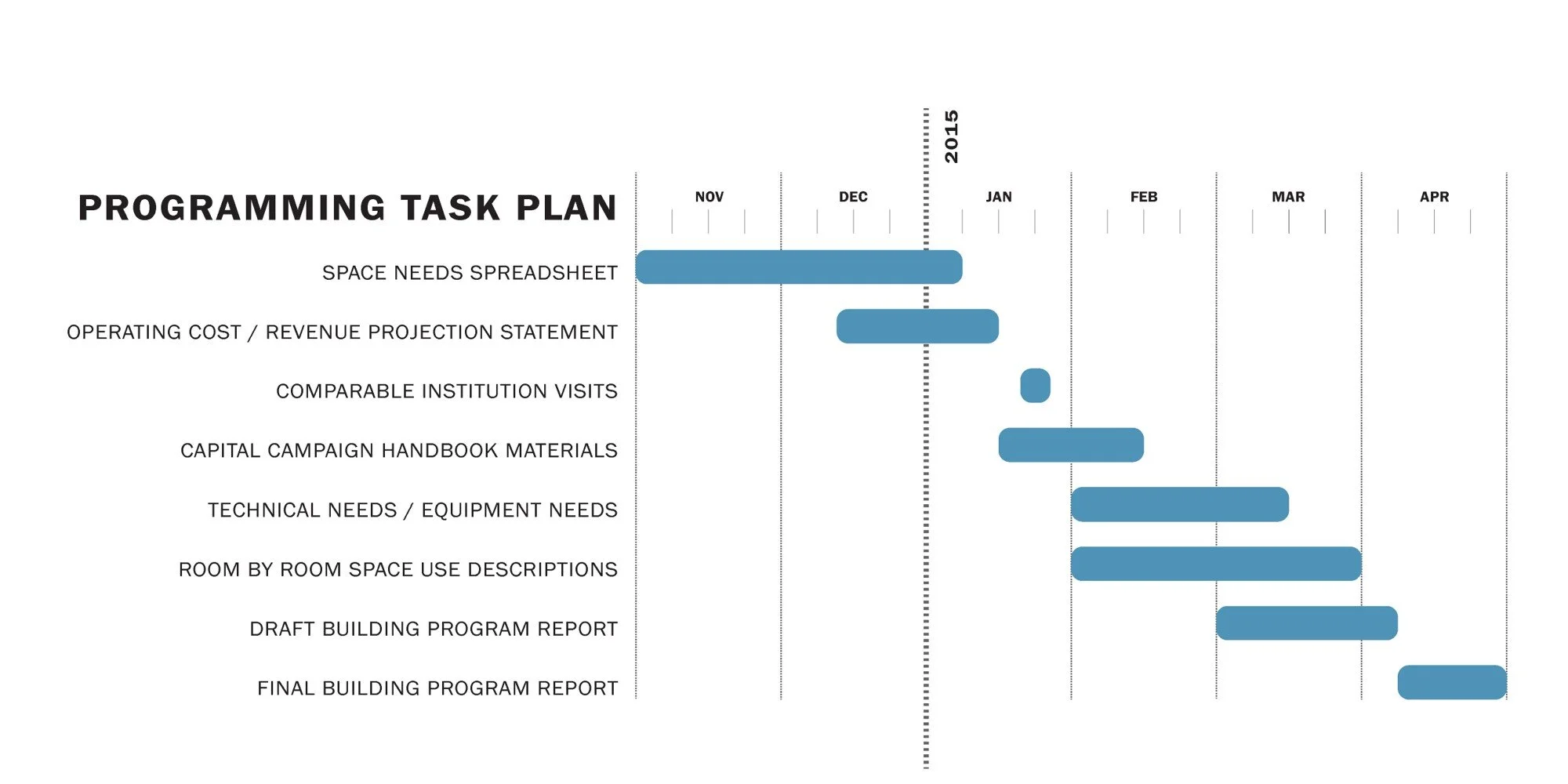

The first step in rectifying this involved assessing what the museum already had, versus what it wanted to do in the future, and assess beyond simple construction costs, how much the new institution would cost operationally. Together, the team developed a comprehensive Programming Task Plan to compartmentalize and order the many tasks at hand.

The Programming Task Plan and Timeline

With this, we drilled down into how visitors might move through the building, through the galleries, and as a crucial comparison, conducted a field trip to comparable institutions with the entire design team and stakeholders. These other museums, many that had just been recently finished, were extremely open about sharing project information. Teams were walked through loading docks, through collection and storage, through the interiors into the galleries and offices. Whatever we were interested in they were able to share with us.

In total we visited the following:

The New Britain Museum of American Art in New Britain, CT

Yale University Art Gallery in New Haven, CT

Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, CT

Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, MA

Addison Gallery of American Art, Andover, MA

A map of the comparable institutions EDR toured with museum planner Marcy Goodwin and stakeholders from the Bruce.

This represented a truly eye-opening event. We were able to measure their galleries, their collection storage, have a peek into how they dealt with issues. In a true display of grace, they also shared their shortcomings, ideas in their original intent that perhaps didn’t work out as well as they had hoped. We took that all into consideration.

In our case at the Bruce, it was done early enough to where it really had an influence on the programming work.

In the end, the programming exercise lasted approximately 5 months, and represented one of the most intense periods of the project. It produced a 500-page document developed by Marcy Goodwin that addressed everything from mission and future vision to every room described in detail, with numbers, a description by their function, their occupancy, their use, the materials that were used in the room, what was being held inside.

Developing a Realistic Program

• Museum Mission and Vision

• Want vs. Need

• Assessing Existing Building Uses vs. Future Uses

• Security Zones

•Projected Museum Program Costs

• Projected Staffing Needs

• Projected Operating Cost

• Space Relationships

• Movement of Objects

• Movement of Visitors

• Movement of Staff

As architects, this became a roadmap for the future.

Supporting Fundraising

As we moved from programming into design, we simultaneously worked closely with the museum on building public support for the project via campaign materials. Pentagram was hired early on to do not only campaign materials, but graphics and wayfinding on the site, and donor recognition within the building — they’ve been a critical partner throughout.

Indeed, one of the things we do as architects involves supporting museums from a donor standpoint. This is especially critical when it comes to donors considering gifts of arts.

We’ve often taken a gallery as it’s being designed, populated it with the art that’s being proposed, and created renderings and VR experiences where the donor can see their donation in the final space as it might be designed and constructed.